Introduction

I watched a series of seminars online attended by the Dalai Lama and a number of prominent Buddhist monks along with several notable western scientists, mostly physicists. Their mutual intention was to share with one another their respective views of the world. At one point the Dalai Lama inquired as to why westerners were looking toward the Far East and Buddhism for spiritual wisdom and enlightenment when their own religion is a very good one.

“The Kingdom of God is Within You” is a book by Leo Tolstoy from which the piece below titled “Christianity Misunderstood By Men Of Science” is derived. I chose the webpage title “The Divine As Misunderstood By Men Of Science” knowing that if I correctly used the word “Christianity” in the title it would largely be ignored for, there has been over the course of the last century or so (partly due to scientific advancements and thinking) a repudiation of Christianity, and religion in general. In fact, one feels they cannot use the word “religion” without seeming archaic so, in contemporary parlance, the word “religion” is often supplanted with the word “spiritual.” Although, “spiritual” often, and more accurately, refers to non-physical beings and realms.

Leslie Taylor

BIOGRAPHY

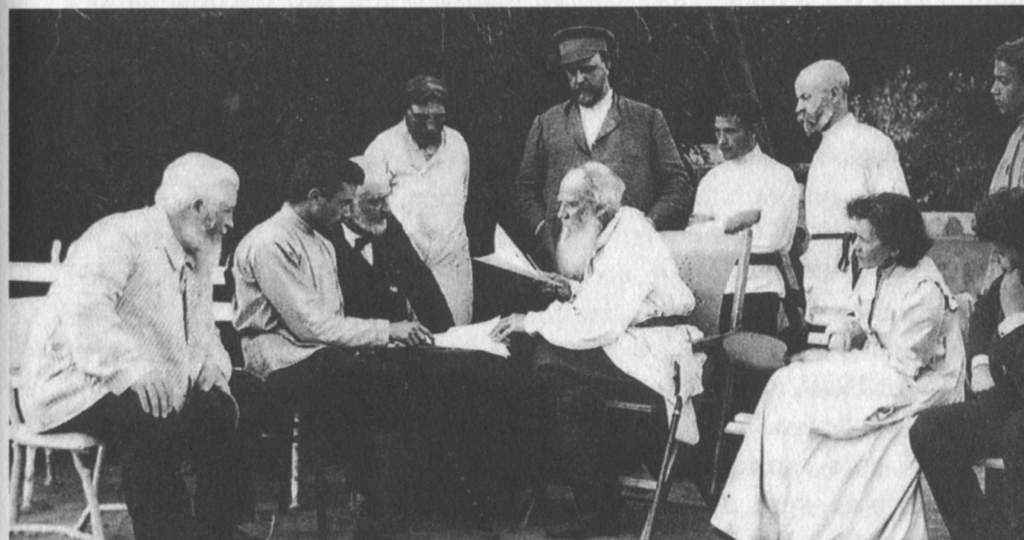

Leo Tolstoy – Count Lev Nidolayevich Tolstoy (1828 – 1910) was a Russian novelist. His best known works are “War and Peace,” “Anna Karenina,” Childhood, Boyhood and Youth,” etc., as well as several novellas such as, “The Death of Ivan Ilyich,” and “Hadji Murad.” He is considered one of the world’s greatest authors. In the 1870s Tolstoy experienced a profound moral crisis followed by what he considered an equally profound spiritual awakening as reported by him in his non-fiction work “A Confession.”

Though born into Russian nobility this crisis led him to abandon his title and, through his interpretations of the ethical teachings of Jesus, he became a fervent Christian anarchist and pacifist. Although, he rejected violent anarchist means of revolution stating that “… there can only be one permanent revolution – a moral one; the regeneration of the inner man.” His conversion from a privileged member of society to the non-violent anarchist was also inspired by his experiences in the army and his travels around Europe as a young man having witnessed a public execution following which he stated to a friend that “… he shall never serve any government anywhere.” His writings on non-violence (expressed here below) were to have a profound impact on Martin Luther King Jr. (1929 – 1968) and Mahatma Gandhi (1883 – 1944).

Tolstoy also became passionately interested in education and founded 13 schools for children of Russian peasants based on the concept of a democratic education. His educational experiments were short lived however, due to harassment by Tsarist secret police.

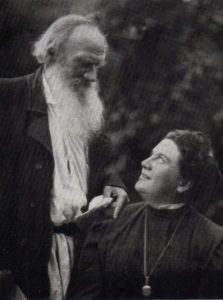

His wife, Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who was 16 years his junior, and he had 13 children, 8 of which survived childhood. Tolstoy’s relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical during which time he sought to reject his inherited and earned wealth. (I have to here mention my admiration of her for keeping their home, family and finances intact during and following his dramatic conversion).

His wife, Sophia Andreevna Behrs, who was 16 years his junior, and he had 13 children, 8 of which survived childhood. Tolstoy’s relationship with his wife deteriorated as his beliefs became increasingly radical during which time he sought to reject his inherited and earned wealth. (I have to here mention my admiration of her for keeping their home, family and finances intact during and following his dramatic conversion).

During his last days he had spoken of and written about dying. At 82 years of age he left his home in the middle of winter, in the dead of the night and died of pneumonia at a train station after a day’s journey by train. The station master took him home to his apartment and his personal doctors were called to the scene. To commemorate this event and the author the train station was named after him: Lev Tolstoy Railway Station.

Tolstoy’s conversion and his book, “My Confession”

Leo Tolstoy has left us, in his book titled “My Confession” an excellent account of his state of motivational anhedonia which led him to his religious conclusions. Anhedonia is a passive, and sometimes (as in Tolstoy’s case) quite sudden, loss of appetite for all life’s values. Tolstoy’s book shows us how this altered and estranged state stimulated his intellect toward an unrelenting and burdensome inquiry seeking philosophical relief. The renowned psychologist William James (1842 – 1910) in his classic book “The Varieties of Religious Experience” describes Tolstoy’s case as such: “… that whatever in life had any meaning for him was for a time wholly withdrawn. Yet, there are some whom this state eventually leads to the profoundest astonishment.” For them, as James describes it, the strangeness is wrong and the unreality cannot be. A mystery is concealed and a metaphysical explanation must exist. An urgent wondering and question is thus set up; a theoretic activity in a desperate effort to get into right relations with the matter. The anhedonia sufferer is often led to what becomes for them, a satisfying religious solution, a religious conversion.

The phenomenon of religious conversion, or regeneration are, according to James, not infrequently, a consequence, not the origin, of the [spiritual] change operated in the individual. A transformation of the view of all of nature upon the renewed perceiver is as though a new Heaven seems to shine upon a new Earth.

I had a similar experience decades ago which lasted three days. And, like Tolstoy, It came on suddenly and unexpectedly and, I was in such an agitated state I could not relax for a moment needing to intellectually (or so I concluded for there seemed no other way) seek assurances that life was indeed meaningful, which I did in fact accomplish. I considered it then, and still do to this day, a spiritual crisis and it did result in a spiritual solution. Yet, neither the crisis nor the solution was nearly as dramatic as Tolstoy’s. It has since become my understanding that this is not at all an uncommon experience. Tolstoy’s lasted for over a year and I cannot imagine having experienced such unrelenting dread and fear for so long a period of time as that. But, being the brilliant individual that he was this experience led to some very profound and meaningful works produced by him; and derived from those works are the two essays here.

From James’s book we learn that at about the age of 50, Tolstoy relates that he began to experience moments of perplexity, of what he calls an arrest; as if he knew not how to live or what to do. Prior to this, he claims, life had been enchanting; and now, flat sober, more than sober; dead. He writes:

“All this took place at a time when so far as all my outer circumstances went, I ought to have been completely happy. I had a good wife who loved me and whom I loved, good children and a large property which was continually increasing with no effort on my part. I was more respected by my kinsfolk and acquaintances than I had ever been. I was loaded with praise by strangers and, without exaggeration, I could believe my name already famous. Moreover, I was neither insane nor ill. On the contrary, I possessed a physical and mental strength which I have rarely met in persons of my age. I could mow as well as the peasants, I would work with my brain eight hours uninterruptedly and feel no bad effects.”

“All this took place at a time when so far as all my outer circumstances went, I ought to have been completely happy. I had a good wife who loved me and whom I loved, good children and a large property which was continually increasing with no effort on my part. I was more respected by my kinsfolk and acquaintances than I had ever been. I was loaded with praise by strangers and, without exaggeration, I could believe my name already famous. Moreover, I was neither insane nor ill. On the contrary, I possessed a physical and mental strength which I have rarely met in persons of my age. I could mow as well as the peasants, I would work with my brain eight hours uninterruptedly and feel no bad effects.”

Tolstoy continues, “And yet I could give no reasonable meaning to any of the activities of my life. And, I was surprised that I had not understood this from the very beginning. My state of mind was as if some wicked and stupid jest was being played upon my mind by someone. This is no fable, but the literal incontestable truth which everyone must understand. What will be the outcome of what I do today? Of what I shall do tomorrow? Of all my life? Why should I live? Why should I do anything? Is there in life any purpose in which the inevitable death which awaits me does not undo and destroy? These questions are the simplest in the world. From the naïve child to the wisest old man, they are in the soul of every human being. Without an answer, it is impossible, as I experience it, for life to go on.”

“But perhaps, I’ve often said to myself, there may be something I have failed to notice or to comprehend. It is not possible that this condition of despair should be natural to mankind. So I sought for an explanation in all the branches of knowledge acquired by men. I questioned painfully and protractedly and, with no idle curiosity. I sought, not with indolence, but laboriously and obstinately for days and nights together. I sought like a man who is lost and seeks to save himself – and I found nothing. I became convinced, moreover, that all those who before me had sought for an answer in the sciences have also found nothing. And not only this, but that they recognized that the very thing which was leading me to despair: that being that the meaningless absurdity of life is the only incontestable knowledge accessible to man.”

James goes to tell us that, to prove this point, Tolstoy quotes the Buddha, Solomon, and Schopenhauer. And, he finds only four ways in which men of his own class and society are accustomed to meet the situation: with mere animal blindness, or reflective Epicureanism, snatching what it can while the day lasts (a more deliberate stupefaction then the first), or manly suicide, or merely weakly and plaintively clinging to the bush of life. And, suicide seemed to be the consistent course dictated by the logical, rational, intellect.

“Yet,” says Tolstoy, “whilst my intellect was working, something else in me was working too, and kept me from the deed – a consciousness of life, as I may call it, which was like a force that obliged my mind to fix itself in another direction and draw me out of my state of despair. During the whole course of this year, when I almost unceasingly kept asking myself how to end the business, whether by the rope or by the bullet, during all that time, alongside of all those movements of my ideas and observations, my heart kept languishing with another pinning emotion. I can call this by no other name than that of a thirst for God. This craving for God … came from my heart. It was like the feeling of an orphan isolated in the midst of all these things that were so foreign. And, this feeling was mitigated by the hope of finding the assistance of someone.”

“Yet,” says Tolstoy, “whilst my intellect was working, something else in me was working too, and kept me from the deed – a consciousness of life, as I may call it, which was like a force that obliged my mind to fix itself in another direction and draw me out of my state of despair. During the whole course of this year, when I almost unceasingly kept asking myself how to end the business, whether by the rope or by the bullet, during all that time, alongside of all those movements of my ideas and observations, my heart kept languishing with another pinning emotion. I can call this by no other name than that of a thirst for God. This craving for God … came from my heart. It was like the feeling of an orphan isolated in the midst of all these things that were so foreign. And, this feeling was mitigated by the hope of finding the assistance of someone.”

James tells us of the process, intellectual as well as emotional, which, beginning with this idea of God, led to Tolstoy’s recovery. Yet, he goes on to explain that when disillusionment has gone as far as this there is seldom a satisfactory resolve. For, once one has tasted the fruit of the tree, the happiness of Eden never comes again. According to James, the happiness that does come is not due to the simple ignorance of ill, but something vastly more complex: including evil as one of its elements. But, finding evil is no stumbling block because it is now seen as swallowed up in supernatural good. The process is one of redemption and not of a mere reversion back to natural health. The sufferer, when saved, is saved by what seems to him to be a deeper kind of consciousness than he knew before; a second birth.

******

CHRISTIANITY AS MISUNDERSTOOD BY MEN OF SCIENCE

by Leo Tolstoy

The false ideas of men of science on Christianity proceed from their conviction that they have an infallible method of criticism from which come two misconceptions in regard to Christian doctrine.

The first misconception is that the teaching cannot be put into practice due to Christianity directing life in a way different from that of the “social theory of life” (which Tolstoy later elaborates on). To this Tolstoy also explains that Christianity holds up ideals and does not lay down rules. To the “animal force of man” (which Tolstoy also later, further clarifies) Christ’s teachings adds the “consciousness of a Divine Force.” And, to the criticism by men of science that Christianity seems to destroy the possibility of human life (given the nature and strength if its spiritual teachings) Tolstoy explains, only when the ideal held up is mistaken for rule. Yet, to that he adds that the ideal must not be lowered. Life, he continues, according to Christ’s teaching, is movement. The second misconception regarding the ideal and the precepts (or principals) of Christ’s teachings regards the replacing of love and service to humanity with love and service to God. For, men of science imagine that their doctrine of service to humanity and Christianity are identical. Yet, the doctrine of service to humanity is based on the social conception, or theory, of life. Love for humanity, logically deduced from love for self (the animal conception of life) has no meaning. For, humanity is a fiction: marginalized; separated from others, all else and from God, and temporal; mortal, and as well constrained by the ‘laws’ of time and space. Whereas Christian love deduced from love of God finds its object in the whole and not in humanity alone. In other words, Christianity teaches man to live in accordance with his Divine Nature. It shows that the essence of the soul of man is love, and that his happiness ensues from love of God, whom he recognizes as love within himself.

Now I will speak of the other view of Christianity which hinders the true understanding of it, writes Tolstoy – the scientific view:

Churchmen substitute for Christianity the version they have framed of it for themselves, and this view of Christianity they regard as the one infallibly true one. Thus, men of science regard as Christianity only the tenets (religious beliefs) held by the different churches in the past and present and, finding that these tenets have lost all the significance of Christianity, they perceive it as a religion which has outlived its age.

This is as true today as it was 100 years ago in Tolstoy’s time. I know of many scientists that cite antiquated religious belief systems claiming all then are unworthy of intelligent, rational considerations for they have since been scientifically disproven.

(1)

To see clearly how impossible it is to understand the Christian teaching from such a point of view, one must form for oneself an idea of the place actually held by religions in general, by the Christian religion in particular, in the life of mankind and of the significance attributed to religions by science. Just as the individual man cannot live without having some theory of the meaning of his life, and is always, though often unconsciously, framing his conduct in accordance with the meaning he attributes to his life, so too associations of men, nations, living in similar conditions cannot but have theories of the meaning of their associated life and conduct ensuing from those theories. And, as the individual man, when he attains a fresh stage of growth, inevitably changes his philosophy of life. The grown-up man sees a different meaning in it from the child, so too associations of men, nations, are bound to change their philosophy of life and the conduct ensuing from their philosophy to correspond with their development.

The difference, regarding this, between the individual man and humanity as a whole, lies in the fact that the individual, in forming the view of life proper to the new period of life on which he is entering and the conduct resulting from it, benefits by the experience of men who have lived before him, who have already passed through the stage of growth upon which he is entering. But humanity cannot have this aid, because it is always moving along a hitherto untrodden track and has no one to ask how to understand life, and how to act in the conditions on which it is entering into and through which no one has ever passed before.

Nevertheless, just as a man with wife and children cannot continue to look at life as he looked at it when he was a child, so too in the face of the various changes that are taking place: the greater density of population, the establishment of communication between different peoples, the improvements of the methods of the struggle with nature, and the accumulation of knowledge, and so on, humanity cannot continue to look at life as of old and must frame a new theory of life, from which conduct may follow adapted to the new conditions on which it has entered and is entering.

(2)

To meet this need humanity has the special power of producing men who give a new meaning to the whole of human life – a theory of life from which follow new forms of activity quite different from all that preceded them. The formation of this philosophy of life appropriate to humanity in the new conditions on which it is entering, and of the practice resulting from it, is what is called religion. And therefore, in the first place, religion is not, as science imagines, a manifestation which at one time corresponded with the development of humanity, but is afterward outgrown by it. Rather, it is a manifestation always inherent in the life of humanity, and is as indispensable, as inherent in humanity at the present time as at any other time.

Religion is always the theory of the practice of the future and not of the past, and therefore it is clear that investigation of past manifestations cannot in any case grasp the essence of religion. The essence of every religious teaching lies not in the desire for a symbolic expression of the forces of nature, nor in the dread of these forces, nor in the craving for the marvelous, nor in the external forms in which it is manifested (churches, sacraments, idols, etc.) as men of science imagine. The essence of religion lies in the faculty of men foreseeing and pointing out the path of life along which humanity must move in the discovery of a new theory of life, as a result of which the whole future conduct of humanity is changed and different from all that has been before. This faculty of foreseeing the path along which humanity must move, is common to a greater or lesser degree to all men. But, in all times there have been men in whom this faculty was especially strong, and these men have given clear and definite expression to what all men felt vaguely, and formed a new philosophy of life from which new lines of action followed for hundreds and thousands of years.

(3)

The Three Philosophies of Life

Of such philosophies of life we know three; two have already been passed through by humanity, and the third is that which we are passing through now in Christianity. These philosophies of life are three in number, and only three, not because we have arbitrarily brought the various theories of life together under these three heads, but because all men’s actions are always based on one of these three views of life for, we cannot view life otherwise than in these three ways.

These three views of life are as follows:

- First, embracing the individual, or the animal view of life.

- Second, embracing the society, or the pagan view of life.

- Third, embracing the whole, or the Divine view of life.

In the first theory of life a man’s life is limited to his one individuality; the aim of life is the satisfaction of the will of this individuality. In the second theory of life a man’s life is limited not to his own individuality, but to certain societies and classes of individuals: the family, the clan, the tribe, the nation; the aim of life is limited to the satisfaction of the will of those associations of individuals. In the third theory of life a man’s life is limited not to societies and classes of individuals, but extends to the principle and source of life – to God. These three conceptions of life form the foundation of all the religions that exist or have existed.

The savage recognizes life only in himself and his personal desires. His interest in life is concentrated on himself alone. The highest happiness for him is the fullest satisfaction of his desires. The motive power of his life is personal enjoyment. His religion consists in propitiating in worshiping his gods, whom he imagines as persons living only for their personal aims.

The civilized pagan recognizes life not in himself alone, but in societies of men–in the family, the clan, the tribe, the nation and sacrifices his personal good for these societies. The motive power of his life is glory. His religion consists in the exaltation of the glory of those who are allied to him: the founders of his family, his ancestors, his rulers and, in worshiping gods who are exclusively protectors of his family, his nation, his government [see footnote].

Footnote: The fact that so many varied forms of existence: the life of the family, of the clan, of the tribe, of the state, and even the life of humanity theoretically conceived by the Positivists [positivism is a philosophical theory based on physicalism, or materialism], are actually contrary to the unity of this theory of life. All these varied forms of life are founded on the same conception: that the life of the individual is not a sufficient aim of life: that the meaning of life can be found only in societies of individuals.

The man who holds the divine theory of life recognizes life not in his own individuality, and not in societies of individualities (in the family, the clan, the nation, or the government) but, in the eternal undying source of life – in God; and to fulfill the will of God he is ready to sacrifice his individual and family and social welfare. The motor power of his life is love. And his religion is the worship in deed and in truth of the principle of the whole – God.

The whole historic existence of mankind is nothing else than the gradual transition from the personal, animal conception of life to the social conception of life, and from the social conception of life to the Divine conception of life. The whole history of the ancient peoples, lasting through thousands of years and ending with the history of Rome, is the history of the transition from the animal, personal view of life to the social view of life. The whole of history from the time of the Roman Empire and the appearance of Christianity is the history of the transition, through which we are still passing now, from the social view of life to the Divine view of life.

(4)

This view of life is the last, and founded upon it is the Christian teaching, which is a guide for the whole of our life and lies at the root of all our activity, practical and theoretic. Yet men of what is falsely called science, pseudo-scientific men, looking at it only in its externals [matter and the forces that act upon matter – materialists] regard it as something outgrown and having no value for us. Reducing Christianity to its dogmatic side only–to the doctrines of the Trinity, the redemption, the miracles, the Church, the sacraments, and so on–men of science regard it as only one of an immense number of religions which have arisen among mankind, and now they say, having played out its part in history, it is outliving its own age and fading away before the light of science and of true enlightenment.

We come here upon what, in a large proportion of cases, forms the source of the grossest errors of mankind. Men on a lower level of understanding when brought into contact with phenomena of a higher order, instead of making efforts to understand them, to raise themselves up to the point of view from which they must look at the subject, judge it from their lower standpoint. And, the less they understand what they are talking about, the more confidently and unhesitatingly they pass judgment on it. To the majority of learned then, looking at the living, moral teaching of Christ from the lower standpoint of the conception of life, this doctrine appears as nothing but very indefinite and incongruous combination of Indian asceticism, Stoic and Neoplatonic philosophy, and insubstantial anti-social visions, which have no serious significance for our times. Its whole meaning is concentrated for them in its external manifestations–in Catholicism, Protestantism, in certain dogmas, or in the conflict with the temporal power [meaning spatial-temporal properties]. Estimating the value of Christianity by these phenomena is like a deaf man’s judging of the character and quality of music by seeing the movements of the musicians.

The result of this is that all these scientific men, from Kant, Strauss, Spencer, and Renan on down, do not understand the meaning of Christ’s sayings, do not understand the significance, the object, or the reason of their utterance, do not understand even the question to which they form the answer. Yet, without even taking the pains to enter into their meaning, they refuse, if unfavorably disposed, to recognize any reasonableness in his teachings. Or, if they want to treat them indulgently they condescend, from the height of their superiority, to correct them on the supposition that Christ meant to express precisely their own ideas, but did not succeed in doing so. They behave to his teachings much as self-assertive people talk to those whom they consider beneath them, often supplying their companions’ words: “Yes, what you mean to say is this and that.” This correction is always with the aim of reducing the teaching of the higher, divine conception of life to the level of the lower, state conception of life.

The result of this is that all these scientific men, from Kant, Strauss, Spencer, and Renan on down, do not understand the meaning of Christ’s sayings, do not understand the significance, the object, or the reason of their utterance, do not understand even the question to which they form the answer. Yet, without even taking the pains to enter into their meaning, they refuse, if unfavorably disposed, to recognize any reasonableness in his teachings. Or, if they want to treat them indulgently they condescend, from the height of their superiority, to correct them on the supposition that Christ meant to express precisely their own ideas, but did not succeed in doing so. They behave to his teachings much as self-assertive people talk to those whom they consider beneath them, often supplying their companions’ words: “Yes, what you mean to say is this and that.” This correction is always with the aim of reducing the teaching of the higher, divine conception of life to the level of the lower, state conception of life.

They usually say that the moral teaching of Christianity is very fine, but over exaggerated; that to make it quite right we must reject all in it that is superfluous and unnecessary to our manner of life. “The doctrine, or teaching, that asks too much, and requires what cannot be performed, is worse than that which requires of men what is possible and consistent with their powers.” These learned interpreters of Christianity maintain, repeating what was long ago asserted, and could not but be asserted, by those who crucified the Teacher because they did not understand him.

(5)

It seems that in the judgment of the learned men of our time, the Hebrew law–a tooth for a tooth, and an eye for an eye–is a law of just retaliation, known to mankind five thousand years before the law of holiness which Christ taught in its place. It seems that all that has been done by those men who truly understood Christ’s teaching and lived in accordance with such an understanding of it; all that has been said and done by all true Christians, by all the Christian saints, all that is now reforming the world in the shape of socialism and communism, is simply an exaggeration, according to these learned men, and not worth talking about.

Let us recall the place and time of Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910) and events that followed: In 1905 revolution broke out in St. Petersburg, but Czar Nicholas quickly put an end to it. The day was called Bloody Sunday. Then in 1908 the Russian mystic Rasputin [image left] healed Czar Nicholas’ sick son gaining him considerable influence with the Czar’s family. Still, Rasputin purportedly wasn’t a good man and many in Russia hated him, putting the people at odds with the Czar. In 1914 World War I began and Russia’s involvement led to over 3 million Russians killed. In 1917 the people were growing increasingly unhappy due to lack of food and other supplies and they began protesting and organized strikes, refusing to do their work. These difficulties along with the Army’s severe losses led to the fall of the House of Romanov. Lenin, who led the Social-Democrat Labor Party, soon took control of Russia. In 1918 Lenin signed a treaty taking Russia out of WWI. Later that year he had Czar Nicholas and his family killed.

Let us recall the place and time of Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910) and events that followed: In 1905 revolution broke out in St. Petersburg, but Czar Nicholas quickly put an end to it. The day was called Bloody Sunday. Then in 1908 the Russian mystic Rasputin [image left] healed Czar Nicholas’ sick son gaining him considerable influence with the Czar’s family. Still, Rasputin purportedly wasn’t a good man and many in Russia hated him, putting the people at odds with the Czar. In 1914 World War I began and Russia’s involvement led to over 3 million Russians killed. In 1917 the people were growing increasingly unhappy due to lack of food and other supplies and they began protesting and organized strikes, refusing to do their work. These difficulties along with the Army’s severe losses led to the fall of the House of Romanov. Lenin, who led the Social-Democrat Labor Party, soon took control of Russia. In 1918 Lenin signed a treaty taking Russia out of WWI. Later that year he had Czar Nicholas and his family killed.

After eighteen hundred years (up to Tolstoy’s time and is still so in the present) of education in Christianity, the civilized world, as represented by its most advanced thinkers, holds the conviction that the Christian religion is a religion of dogmas; that its teaching in relation to life is unreasonable, and is an exaggeration, subversive of the real lawful obligations of morality consistent with the nature of man; and that very doctrine of retribution which Christ rejected is more practically useful for us.

To learned men the doctrine of non-resistance to evil by force is exaggerated and even irrational. They do not see that to say that the doctrine of non-resistance to evil is an exaggeration in Christ’s teaching is like saying that the ratio of the radii to the circumference of a circle is an exaggeration in the definition of a circle. And those who speak thus are acting precisely like a man who, having no idea of what a circle is, should declare that this requirement, that every point of the circumference should be an equal distance from the center, is exaggerated. To advocate the rejection of Christ’s command of non-resistance to evil as a necessary adaptation given the needs of life, implies a misunderstanding of the teaching of Christ.

They do not understand that this teaching is the institution of a new theory of life, aptly corresponding to the new conditions on which men have entered from eighteen hundred years ago (up to the present) and also the definition of the new conduct of life which results from it. They do not believe that Christ meant to say what he said; or he seems to them to have said what he said in the Sermon on the Mount and in other places accidentally, or through his lack of intelligence, or of cultivation.

They do not understand that this teaching is the institution of a new theory of life, aptly corresponding to the new conditions on which men have entered from eighteen hundred years ago (up to the present) and also the definition of the new conduct of life which results from it. They do not believe that Christ meant to say what he said; or he seems to them to have said what he said in the Sermon on the Mount and in other places accidentally, or through his lack of intelligence, or of cultivation.

[Footnote: Here, for example, is a characteristic view of that kind from the American journal “The ARENA” (October, 1890): “New Basis of Church Life.” Treating of the significance of the Sermon on the Mount and non-resistance to evil in particular, the author, like the churchmen, obscures its significance, stating that:

“Christ in fact preached complete communism and anarchy; but one must learn to regard Christ always in his historical and psychological significance. Like every advocate of the love of humanity, Christ went to the furthest extreme in his teaching. Every step forward toward the moral perfection of humanity is always guided by men who see nothing but their vocation. Christ, in no disparaging sense be it said, had the typical temperament of such a reformer. And therefore we must remember that his precepts cannot be understood literally as a complete philosophy of life. We ought to analyze his words with respect for them, but in the spirit of criticism, accepting what is true, etc. Christ would have been happy to say what he ought, but he was not able to express himself as exactly and clearly as we can in the spirit of criticism, and therefore let us correct him. All that he said about meekness (humility), sacrifice, lowliness, not caring for the morrow, was said by accident, through lack of knowing how to express himself scientifically.”]

(6)

For example:

Matt. vi. 25-34: “Therefore I say unto you, Take no thought for your life, what ye shall eat, or what ye shall drink; nor yet for your body, what ye shall put on. Is not the life more than meat, and the body than rainment? Behold the fouls of the air; for they sow not, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns; yet your heavenly Father feedeth them. Are ye not much better than they? Which of you by taking these thoughts can add one cubit onto his stature? And why take ye thought for rainment? Consider the lilies of the field how they grow; they toil not, neither do they spin; and yet I say unto you, that even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Wherefore, if God so clothe the grass of the field, which today is, and tomorrow is cast into the oven, shall he not much more clothe you, O ye of little faith? Therefore take no thought saying, What shall we eat? or, What shall we drink? or, Wherewithal shall we be clothed? (After all, these things do the Gentiles seek). For your heavenly Father knoweth that ye have need of all these things. But seek ye first the kingdom of God, and His righteousness, and all these things shall be added unto you. Take therefore no thought for the morrow; for the morrow shall take thought for the things of itself.”

Luke xii. 33-34: “Sell that ye have, and give alms; provide yourselves bags which wax not old [that won’t wear out], a treasure in the heavens that faileth not, where no thief approacheth, neither moth corrupteth. For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also. Sell all thou hast and follow me; and he who will not leave father, or mother, or children, or brothers, or fields, or house, he cannot be my disciple. Deny thyself, take up thy cross each day and follow me. My meat [sustenance] is to do the will of him that sent me, and to perform his works. Not my will, but thy will be done; not what I will, but as thou wilt. Life is to do not one’s will, but the will of God.”

Tolstoy explains: All these principles appear to men who regard them from the standpoint of a lower conception of life as the expression of an impulsive enthusiasm, having no direct application to life. These principles, however, follow from the Christian theory of life, just as logically as the principles of paying a part of one’s private gains to the commonwealth and of sacrificing one’s life in defense of one’s country follow from the state, the pagan, theory of life.

(Tolstoy here is pointing out what sacrifices governments, and in particular their military, demands of its citizens and for what purpose? To achieve glory by killing).

As the man of the state conception of life said to the savage: Reflect, bethink yourself! The life of your individuality cannot be true life, because that life is pitiful and passing. But the life of a society and succession of individuals, family, clan, tribe, or state, goes on living, and therefore a man must sacrifice his own individuality for the life of the family or the state. In exactly the same way the Christian doctrine says to the man of the social, state, pagan conception of life, repent, bethink [reflect] yourself, or you will be ruined. Understand that this casual, personal life which now comes into being, and tomorrow is no more, can have no permanence; that no external means, no construction of it can give it consecutiveness and permanence. Take thought and understand that the life you are living is not real life – the life of the family, of society, of the state will not save you from annihilation. The true, the rational life is only possible for man according to the measure in which he can participate, not in the family or the state, but in the source of life – the Father; according to the measure in which he can merge his life in the life of the Father. Such is undoubtedly the Christian conception of life, visible in every utterance of the Gospel.

(7)

![th[7]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/th7-247x300.jpg) One may not share this view of life, one may reject it, one may show its inaccuracy and its erroneousness, but we cannot judge the Christian teaching without mastering this view of life. Still less, one cannot criticize a subject on a higher plane from a lower point of view. From the basement one cannot judge of the effect of the spire. But this is just what the learned critics of the day try to do. For they share the same erroneous idea of the orthodox believers that they are in possession of certain infallible means for investigating and validating a subject. They fancy that if they apply their so-called scientific methods of criticism, there can be no doubt of their conclusion being correct. This testing the subject by the fancied infallible method of science is the principal obstacle to understanding the Christian religion for unbelievers, for so-called educated people. From this follow all the mistakes made by scientific men about the Christian religion, and especially two strange misconceptions which, more than everything else, hinder them from a correct understanding of it.

One may not share this view of life, one may reject it, one may show its inaccuracy and its erroneousness, but we cannot judge the Christian teaching without mastering this view of life. Still less, one cannot criticize a subject on a higher plane from a lower point of view. From the basement one cannot judge of the effect of the spire. But this is just what the learned critics of the day try to do. For they share the same erroneous idea of the orthodox believers that they are in possession of certain infallible means for investigating and validating a subject. They fancy that if they apply their so-called scientific methods of criticism, there can be no doubt of their conclusion being correct. This testing the subject by the fancied infallible method of science is the principal obstacle to understanding the Christian religion for unbelievers, for so-called educated people. From this follow all the mistakes made by scientific men about the Christian religion, and especially two strange misconceptions which, more than everything else, hinder them from a correct understanding of it.

One of these misconceptions is that the Christian moral teaching cannot be carried out, and that therefore it has either no force at all – that is, it should not be accepted as the rule of conduct or, it must be transformed, adapted to the limits within which its fulfillment is possible in our society. Another misconception is that the Christian doctrine of love of God, and therefore of his service to, is an obscure, mystic principle which gives no definite object for love and should therefore be replaced by the more exact and comprehensible principles of love for men and the service of humanity.

The first misconception, in regard to the impossibility of following the principle, is the result of men of the state conception of life unconsciously taking that conception as the standard by which the Christian religion directs men. And, regarding the Christian principle of [divine] perfection as the rule by which that life is to be ordered; they think and say that to follow Christ’s teaching is impossible, because the complete fulfillment of all that is required by this teaching would put an end to life. In other words, “If a man were to carry out all that Christ teaches, he would destroy his own [requirements for physical] life; and, if all men carried it out then the human race would come to an end,” they say. “For, if we take no thought for the morrow, what we shall eat and what we shall drink, and wherewithal we shall be clothed? If we do not defend our life, nor resist evil by force, lay down our life for others (as in the military) and observe perfect chastity, the human race cannot exist,” they say.

And they are perfectly right if they take the principle of perfection given by Christ’s teaching as a rule which everyone is bound to fulfill, just as they do in the state principles of life everyone is bound to carry out the rule of paying taxes, supporting the law, and so on. This misconception is based precisely on the fact that the teaching of Christ guides different men differently, derived from which the precepts founded on the lower conception of life guide men. The precepts of the state conception of life only guide men by requiring of them an exact fulfillment of rules or laws. Christ’s teaching guides men by pointing them toward the infinite perfection of their heavenly Father, to which every man independently and voluntarily struggles, whatever the degree of his imperfection in the present.

(8)

The misunderstanding of men who judge of the Christian principle from the point of view of the state principle, is based on the supposition that the perfection which Christ points to can be fully attained and, they then ask themselves (just as they naturally ask the same question on the supposition that state laws will be carried out) what will be the result of all this being carried out? This supposition cannot be made, because the perfection held up to Christians is infinite and can never be attained. And, Christ lays down his principle having in view the fact that absolute perfection can never be attained, but that striving toward absolute, infinite perfection will continually increase the blessedness of men, and that this blessedness may be increased to infinity thereby.

Christ is teaching not angels, but men, living and moving in the animal [physical] life. And so to this animal force of movement Christ, as it were, applies the new force – the recognition of Divine perfection – and thereby directs the movement by the resultant of these two forces, the animal and the Divine.

To suppose that human life is going in the direction to which Christ pointed it, is just like supposing that a little boat afloat on a raging river, and directing its course almost exactly against the current, will progress in that direction.

Christ recognizes the existence of both sides of the parallelogram, of both forces of which the life of man is compounded: the force of his animal nature and the force of his consciousness of his Kinship with God. Saying nothing of the animal force which asserts itself, remains always the same independent of human will, Christ speaks only of the Divine Force, calling upon a man to know it more closely, to set it freer within himself from all that retards it, and to carry it to a higher degree of intensity.

life of man is compounded: the force of his animal nature and the force of his consciousness of his Kinship with God. Saying nothing of the animal force which asserts itself, remains always the same independent of human will, Christ speaks only of the Divine Force, calling upon a man to know it more closely, to set it freer within himself from all that retards it, and to carry it to a higher degree of intensity.

In the process of liberating, of strengthening this force, the true life of man, according to Christ’s teaching, consists not in carrying out rules, in carrying out the law. But rather, it consists in striving toward an ever closer approximation to the Divine perfection held up before every man. And, recognized within himself, by every man, in an ever closer and closer approach to the perfect fusion of his will with the will of God; that fusion toward which man strives, and the attainment of which, would be the leaving behind of the world we now know. For, the Divine perfection is the asymptote [definition below] of human life to which it is always striving, and always approaching, though it can only be attained in infinity.

Note: Asymptote: a line that continually approaches a given curve but does not meet it at any finite distance.

(9)

The Christian religion seems to exclude the possibility of life only when men mistake the pointing to an ideal as the laying down of a rule. It is only then that the principles presented in Christ’s teaching appear to be destructive of life. These principles, on the contrary, are the only ones that make true life possible. Without these principles true life could not be possible.

“One ought not to expect so much,” is what people usually say in discussing the requirements of the Christian religion. “One cannot expect to take absolutely no thought for the morrow, as is stated in the Gospel, but only not to take too much thought for it. One cannot give away all to the poor, but one must give away a certain definite part. One need not aim at virginity, but one must avoid debauchery. One need not forsake wife and children, but one must not give too great a place to them in one’s heart,” and so on.

But to speak like this is just like telling a man who is struggling on a swift river and is directing his course against the current, that it is impossible to cross the river rowing against the current, and that to cross it he must float in the direction of the point he wants to reach. Yet, in reality, in order to reach the place to which he wants to go, he must row with all his strength toward a point much higher up.

To let go the requirements of the ideal means not only to diminish the possibility of perfection, but to make an end of the ideal itself. The ideal that has power over men is not an ideal invented by someone; it is the ideal is that which every man carries within his soul. And it is only this ideal of complete infinite perfection that has power over men, and stimulates them to action. Whereas a moderate perfection loses its power of moving men’s hearts.

To let go the requirements of the ideal means not only to diminish the possibility of perfection, but to make an end of the ideal itself. The ideal that has power over men is not an ideal invented by someone; it is the ideal is that which every man carries within his soul. And it is only this ideal of complete infinite perfection that has power over men, and stimulates them to action. Whereas a moderate perfection loses its power of moving men’s hearts.

Christ’s teaching only has power when it demands absolute perfection; that is, the fusion of the divine nature which exists in every man’s soul with the will of God; the union of the Son with the Father. Life according to Christ’s teaching consists of nothing but this setting free of the Son of God, existing in every man, from the animal, and in bringing him closer to the Father.

The animal existence of a man does not constitute human life. Life, according to the will of God, is not just human, animal life for, human life is a combination of the animal life and Divine life. And the more this combination approaches toward the Divine, the more life there is in it.

Life, according to the Christian religion, is a progress toward Divine perfection. No one condition, according to this doctrine, can be higher or lower than another. Every condition, according to this doctrine, is only a particular stage, of no consequence in itself, on the way toward unattainable [in this world] Divine perfection, and therefore in itself it does not imply a greater or lesser degree of life. Increase of life, according to this, consists in nothing but the quickening of the progress toward Divine perfection.

(10)

Therefore, the progress toward perfection of, for example, the publican Zaccheus [a Jewish tax collector for the ancient Romans], of the woman that was a sinner, and of the robber on the cross, implies a higher degree of life than the stagnant righteousness of the Pharisee [a member of an ancient Jewish sect, distinguished by strict observance of the traditional and written law, and commonly held to have pretensions to superior sanctity, and has since come to mean a self-righteous person; a hypocrite].

For, this religion there cannot be rules by which it is obligatory to obey. The man who is at a lower level but is moving onward toward perfection is living a more moral, a better life, is more fully carrying out Christ’s teaching, than the man on a much higher level of morality who is not moving onward toward perfection. It is in this sense that the lost sheep is dearer to the Father than those that were not lost. The prodigal son, the piece of money lost and found again, were more precious than those that were not lost.

![L.Tolstoy_and_S.Tolstaya[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/L.Tolstoy_and_S.Tolstaya1-228x300.jpg) The fulfillment of Christ’s teaching consists in moving away from self toward God. It is obvious that there cannot be definite laws and rules for this fulfillment of the teaching. Every degree of perfection and every degree of imperfection are equal in it; no obedience to laws constitutes a fulfillment of this doctrine, and therefore for it there can be no binding rules and laws.

The fulfillment of Christ’s teaching consists in moving away from self toward God. It is obvious that there cannot be definite laws and rules for this fulfillment of the teaching. Every degree of perfection and every degree of imperfection are equal in it; no obedience to laws constitutes a fulfillment of this doctrine, and therefore for it there can be no binding rules and laws.

From this fundamental distinction between the religion of Christ and all preceding religions based on the state conception of life, follows a fundamental and corresponding difference between the special precepts of the state theory and the Christian precepts. The precepts of the state theory of life insist, for the most part, on certain practical prescribed acts by which men feel justified and, hopefully, secure in their being right.

![Parini-t_CA0-articleInline[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Parini-t_CA0-articleInline1.jpg) Yet, the Christian precepts (excluding the commandment of love which is not a precept in the strict sense of the word, but the expression of the very essence of the religion) are the five commandments of the Sermon on the Mount. Expressed in the negative form, they show only what at a certain stage of development of humanity men may not do (“Thou shalt not …”). These commandments are, as it were, signposts on the endless road toward perfection, toward which humanity is moving, showing the point of perfection which is possible at a certain period in the development of humanity.

Yet, the Christian precepts (excluding the commandment of love which is not a precept in the strict sense of the word, but the expression of the very essence of the religion) are the five commandments of the Sermon on the Mount. Expressed in the negative form, they show only what at a certain stage of development of humanity men may not do (“Thou shalt not …”). These commandments are, as it were, signposts on the endless road toward perfection, toward which humanity is moving, showing the point of perfection which is possible at a certain period in the development of humanity.

Christ has given expression in the Sermon on the Mount to the eternal ideal toward which men are spontaneously struggling, and also the degree of attainment of it to which men may reach:

The ideal is not to desire to do ill to anyone, not to provoke ill will, but to love all men. The precept, showing the level below which we cannot fall in the attainment of this ideal, is the prohibition of evil speaking. And that is the first command.

The ideal is perfect chastity, even in thought. The precept, showing the level below which we cannot fall in the attainment of this ideal, is that of purity of married life, avoidance of debauchery. That is the second command.

(11)

The ideal is to take no thought for the future, to live in the present moment. The precept, showing the level below which we cannot fall, is the prohibition of swearing, of promising anything in the future. And that is the third command.

The ideal is to love the enemies who hate us. The precept, showing the level below which we cannot fall, is not to do evil to our enemies, to speak well of them, and to make no difference between them and our neighbors.

All these precepts are indications of what, on our journey to perfection, we are already fully able to avoid, and what we must labor to attain now, and what we ought by degrees to translate into instinctive and unconscious habits. But these precepts, far from constituting the whole of Christ’s teaching and exhausting it, are simply stages on the way to perfection. These precepts must and will be followed by higher and higher precepts on the way to the perfection held up by the religion.

And therefore it is essentially a part of the Christian religion to make demands higher than those expressed in its precepts; and by no means to diminish the demands either of the ideal itself, or of the precepts, as people imagine who judge it from the standpoint of the social, the state, conception of life.

So much for one misunderstanding of the scientific men, in relation to the import and aim of Christ’s teaching. Another misunderstanding arising from the same source consists in substituting love for men in the service of humanity, for the Christian principles of love for and in service to God.

The Christian doctrine to love and serve God and, only as a result of that love, to love and serve one’s neighbor seems to scientific men obscure, mystic, and arbitrary. And they therefore absolutely exclude the obligation of love and service of God holding that the doctrine of love for men, for humanity alone, is far more clear, tangible, and reasonable. Scientific men teach, in theory, that the only good and rational life is that which is devoted to the service of the whole of humanity. That is for them the only import of the Christian doctrine, and to that they reduce Christ’s teaching. They seek confirmation of their own doctrine in the Gospel based on the supposition that the two doctrines are really the same.

This idea is an absolutely mistaken one. The Christian doctrine has nothing in common with the doctrine of the Positivists [positivism is a philosophical theory based on natural phenomena and their properties and relations; physicalism or materialism], Communists, and all the apostles of the universal brotherhood of mankind, based on the general advantage of such a brotherhood. They differ from Christianity especially in Christianity’s having a firm and clear basis in the human soul, while love for humanity is only a theoretical deduction from analogy (corresponding to the materialist view of life). The doctrine of love for humanity alone is based on the social conception of life.

(12)

The essence of the social conception of life consists in the transference of the aim of the individual (the animal) view of life to the life of societies of individuals: the family, the clan or tribe, the state. This transference is accomplished easily and naturally in its earliest forms, in the transference of the aim of life from the individual to the family and the clan. The transference to the state is more difficult and requires special training. And, the transference of the sentiment to the nation is the furthest limit which the process can reach.

The essence of the social conception of life consists in the transference of the aim of the individual (the animal) view of life to the life of societies of individuals: the family, the clan or tribe, the state. This transference is accomplished easily and naturally in its earliest forms, in the transference of the aim of life from the individual to the family and the clan. The transference to the state is more difficult and requires special training. And, the transference of the sentiment to the nation is the furthest limit which the process can reach.

To love one’s self is natural to everyone, and no one needs any encouragement to do so. To love one’s clan who support and protect one, to love one’s wife (the joy and help of one’s existence), one’s children (the hope and consolation of one’s life), and one’s parents (who have given one’s life and education), is natural. And such love, though far from being so strong as love of one’s self, is met with pretty often.

To love–for one’s own sake, through personal pride–one’s tribe, though not so natural, is nevertheless common. Love of one’s own people who are of the same blood, the same tongue, and the same religion as one’s self is possible, though far from being so strong as love of self, or even one’s love of family or clan. But love for a nation, such as Turkey, Germany, England, Austria, or Russia is a thing almost impossible. And though it (nationalism) is zealously inculcated, it is only an imagined sentiment; it has no existence in reality. And, at that limit, man’s power of extending his interest ceases and he cannot feel any direct sentiment for that trumped-up entity.

The Positivists, however, and all the apostles of fraternity on scientific principles, without taking into consideration the weakening of sentiment in proportion to the extension of its object, draw further deductions in theory in the same direction. “Since,” they say, “it was for the advantage of the individual to extend his personal interest to the family, the tribe, and subsequently to the state and the nation, it would be still more advantageous to extend his interest in societies of men to the whole of mankind, and so all to live for all of humanity just as men live for the family or the clan.

Theoretically it then follows, indeed, having extended the love and interest for the individual to the family, the tribe, and thence to the state and nation, it would be perfectly logical for men to save themselves the strife and calamities which result from the division of mankind into nations and states by extending their love to the whole of humanity. This would be most logical, and theoretically nothing would appear more natural to its advocates, who do not observe that love is a sentiment which may or may not be felt and it is useless to advocate; and moreover, that love must have an object, and that humanity is not an object.”

(13)

The family, the tribe, even the state were not invented by men, but formed themselves spontaneously, like ant-hills or swarms of bees, and have a real existence. The man who, for the sake of his own animal personality, loves his family, knows those whom he loves: Anna, Dolly, John, Peter, and so on. The man who loves his tribe and takes pride in it, knows that he loves all the Gelphs or all the Ghibelines [see note below]; the man who loves the state knows that he loves France bounded by the Rhine River, and the Pyrenees Mountains, and its principal city Paris, and its history, and so on. But the man who loves humanity–what does he love? There is such a thing as a state, as a nation; there is the abstract conception of humanity; but as a concrete idea it does not, and cannot exist.

![220px-Guelfi_e_ghibellini[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/220px-Guelfi_e_ghibellini1.jpg) Note: The Gelphs and the Ghibelines were two familial factions; one supporting the Pope and the other, the Holy Roman Empire in the Italian city states of central and northern Italy during the 12th and 13th century. The split between these two families was an important factor affecting the political, ruling policies of Medieval Italy. The struggle for power between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Emperor began in 1075 ending in 1122. The Gelphs and Ghibelines continued in their antagonisms toward one and another until the 15th century.

Note: The Gelphs and the Ghibelines were two familial factions; one supporting the Pope and the other, the Holy Roman Empire in the Italian city states of central and northern Italy during the 12th and 13th century. The split between these two families was an important factor affecting the political, ruling policies of Medieval Italy. The struggle for power between the Papacy and the Holy Roman Emperor began in 1075 ending in 1122. The Gelphs and Ghibelines continued in their antagonisms toward one and another until the 15th century.

Humanity! Where is the definition of humanity? Where does it end and where does it begin? Does humanity end with the savage, the idiot, the dipsomaniac, or the madman? If we draw a line excluding from humanity its lowest representatives, where are we to draw the line? Shall we exclude the Negroes like the Americans, or the Hindus like some Englishmen, or the Muslims like the Jews, or the Jews like some others? If we include all men without exception, why should we not include also the higher animals, many of whom are superior to the lowest specimens of the human race?

We know nothing of humanity as an eternal object, and we know nothing of its limits. Humanity is a concept and not an object or thing, and therefore it is impossible to love it. It would, doubtless, be very advantageous if men could love humanity just as they love their family. It would be very advantageous, as Communists advocate, to replace the competitive, individualistic organization of men’s activity by a social universal organization, so that each would be for all and all for each. Only there are no motives to lead men to do this.

The Positivists, the Communists, and all the apostles of fraternity on scientific principles advocate the extension to the whole of humanity of the love men feel for themselves, their families, and the state. They forget that the love which they are discussing is a personal love which might expand in a rarefied form to embrace a man’s native country, but which is completely weakened before it can embrace an [artificially margined] state such as Austria, England, or Turkey, and from which, given these borders, we cannot even conceive of love in relation to all of humanity; an absolutely abstract conception.

(14)

“A man loves himself (his animal personality), he loves his family, he may even love his native country. So why should he not love humanity? That would be such an excellent thing. And, by the way, it is precisely what is taught by Christianity.” So think the advocates of Positivist, Communistic, or Socialistic fraternity.

“A man loves himself (his animal personality), he loves his family, he may even love his native country. So why should he not love humanity? That would be such an excellent thing. And, by the way, it is precisely what is taught by Christianity.” So think the advocates of Positivist, Communistic, or Socialistic fraternity.

It would indeed be an excellent thing. But it can never be, for the love that is based on a personal or social conception of life can never extend beyond love for the state. Again, the fallacy of the argument lies in the fact that the social conception of life, on which love for family and nation is founded, rests itself on love of self, and that love grows weaker and weaker as it is extended from self to family, nationality, and state; and in the state we reach the furthest limit beyond which it cannot go.

The necessity of extending the sphere of love is beyond dispute. But in reality the possibility of this love is destroyed by the necessity of extending its objective indefinitely. And thus the insufficiency of personal human love is apparent.

And here the advocates of a Positivist, Communistic, Socialistic fraternity propose to draw upon Christian love to make up the default of this bankrupt human love; but Christian love is realized only in its results, not in its foundations. These advocates propose love for humanity alone, apart from love for God. Such a love cannot exist. There is no motive, no true source, to produce it.

The social conception of life has led men, by a natural transition from love of self, and then to love of family, tribe, state, and nation to a consciousness of the necessity from there to love for humanity, toward an abstract conception which has no definite limits and extends to all living things. And this necessity for a love, which awakens no real kind of sentiment in a man is due to a contradiction. The problem cannot be solved given the structure, the natural limitations, inherent in the social theory of life.

The Christian doctrine in its full significance can alone solve it, by giving a new meaning to life. Christianity recognizes love of self, of family, of nation, and of humanity, and not only of humanity, but of everything living, everything existing; it recognizes the necessity of an infinite extension of the sphere of love. But the object of this love is not found outside self in societies of individuals, in the external world, but within the self, in the Divine Self whose essence is that very love, which the animal self, the individual, is brought to feel the need of; to seek through its consciousness of its own perishable nature.

(15)

The difference between the Christian doctrine and those doctrines which preceded it is that the social doctrine said: “Live in opposition to your nature [understanding by this only the animal nature], make it subject to the external law of family, society, and state.” Christianity says: “Live according to your true nature [understanding by this the Divine nature]; do not make it subject to anything – neither you (an animal self) nor that of others and you will attain the very aim to which you are striving.”

![220px-L.N.Tolstoy_Prokudin-Gorsky[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/220px-L.N.Tolstoy_Prokudin-Gorsky1.jpg) The Christian doctrine brings a man to the elementary consciousness of self, only not of the animal self, but of the Divine Self, the Divine spark, the self as the Son of God, as much God as the Father himself, though confined in an animal husk. The consciousness of being the Son of God, whose chief characteristic is love, satisfies the need for the extension of the sphere of love to which the man of the social conception of life had been brought. For the latter, the welfare of the personality demanded an ever-widening extension of the sphere of love; love was a necessity and was confined to certain objects: self, family, society. With the Christian conception of life, love is not a necessity, marginalized, confined to an object; it is the essential faculty of the human soul. Man loves not because it is his interest to love this or that, but …

The Christian doctrine brings a man to the elementary consciousness of self, only not of the animal self, but of the Divine Self, the Divine spark, the self as the Son of God, as much God as the Father himself, though confined in an animal husk. The consciousness of being the Son of God, whose chief characteristic is love, satisfies the need for the extension of the sphere of love to which the man of the social conception of life had been brought. For the latter, the welfare of the personality demanded an ever-widening extension of the sphere of love; love was a necessity and was confined to certain objects: self, family, society. With the Christian conception of life, love is not a necessity, marginalized, confined to an object; it is the essential faculty of the human soul. Man loves not because it is his interest to love this or that, but …

because love is the essence of his soul; because he cannot but love.

The Christian doctrine shows man that the essence of his soul is love; that his happiness depends not on loving this or that object, but on loving the principle of the whole; God, whom he recognizes within himself as love, and therefore he loves all things and all men. In this is the fundamental difference between the Christian doctrine and the doctrine of the Positivists (again, physicalism, materialism; the scientific view), and all the theorizers about universal brotherhood on those principles other than this Christian principle.

Such are the two primary misunderstandings relating to the Christian religion from which the greater number of false reasonings about it proceed: The first consists in the belief that Christ’s teaching instructs men, like all previous religions, by rules, which they are bound to follow, and that these rules cannot be fulfilled. The second is the idea that the whole purport of Christianity is to teach men to live advantageously together, as one family, and that to attain this we need only follow the rule of love to humanity, dismissing all thought of love of God altogether.

The mistaken notion of scientific men that the essence of Christianity consists in the supernatural, and that its moral teaching is impracticable, constitutes another reason of the failure of men of the present day to understand Christianity.

(16)

******

To continue reading the the next chapter click on the menu above: (O) Leo Tolstoy – The Tough Pacifist, or : https://miraclesforall.com/l-leo-tolstoy-the-tough-pacifist/