Continued from chapter (G) “The Varieties of Religious Experience” by William James – Part II

Lectures XI, XII and XIII – The Value of Saintliness (continued)

The author here points out that as ascetic saints have grown older they usually have shown a tendency to lay less importance on bodily mortifications. Catholic teachers have always professed that, since health is needed for efficiency in God’s service, health must not be sacrificed to mortifications. Today, the general optimism of Protestants and healthy-minded sects consider mortification for mortification’s sake repugnant.

Yet, James continues, he believes that upon a more careful consideration of the whole of the matter, distinguishing between the general good intentions of asceticism and the uselessness of some of the particular acts, of which it may be guilty, may improve it in our esteem. It symbolizes, lamely enough no doubt, but sincerely, the belief that there is an element of real wrongness in the world which is neither to be ignored nor evaded, but which must be squarely met and overcome by an appeal to the soul’s heroic resources and neutralized and cleansed away by suffering. Pain and wrong and death must be fairly met and overcome in the higher religious excitement, or else their sting remains unbroken.

If one has ever taken in the fact of the prevalence of tragic death in this world’s history: freezing, drowning, wild beasts, worse men, hideous diseases, etc., one can with difficulty, continue in their own career of worldly prosperity suspecting that they are somehow outside the game and thus, may then lack the “great initiation.” This is exactly what the ascetic thinks anyway, James alleges, and it therefore voluntarily takes on the initiation. And, healthy-mindedness with its sentimental optimism can hardly be regarded as a serious solution. Phrases of neatness, coziness, and comfort can never give the answer to the sphinx’s riddle [“What walks on four legs in the morning, two legs at noon and three legs at night?”].

James states that here he is leaning only upon mankind’s common instinct for reality which has always held that the world is a theater for heroism. For, in heroism we confront life’s supreme mystery [death] and, we tolerate no one who has no capacity for heroism in any way whatsoever. If on the other hand, regardless of what a man’s frailties may otherwise be, he be willing to risk death, and still more so if he suffers it heroically in the service he has chosen, this fact consecrates him forever. The metaphysical mystery we can logically suppose, says James, of he who feeds on the death that feeds upon men possesses life super eminently, or exceptionally, and thus best meets with the secret demands of the universe. Asceticism faithfully champions this as a legitimate truth.

(91)

The older monastic asceticism occupied itself with pathetic futilities or terminated in the mere egotism of the individual increasing his own perfection. But, James inquires, is it not possible for us to discard most of these older forms of mortification and yet find saner channels for the heroism which inspired them?

In a footnote at the bottom of page 357 of his book James adds a quote from the book “Ramakrishna, His Life and Sayings”: “The vanities of all others may die out, but the vanity of a saint in regards to his sainthood is hard indeed to wear away.”

Does not, James questions, the worship of material luxury and wealth which constitutes so large a portion of the “spirit” of our age [quite true today 100 years later] make somewhat for effeminacy and unmanliness? Is not the commiserating and facetious [frivolous] way in which most children are brought up today – so different from the education of a hundred years ago – in danger, despite its many advantages, of developing a certain trashiness of fiber? [Prophetic perhaps? As is exemplified during sleazy NFL Super Bowl half-time performances, repulsive pornography, tawdry movies, music videos, etc.]. Are there not some points of application for a renovated and revised form of ascetic training the author wonders?

Here James takes us in another direction yet, along the same lines: War and adventure assuredly keeps all who engage in them from treating themselves too tenderly. They demand such incredible efforts, both in degree and in duration, such that the whole scale of motivation alters.

Discomfort and annoyance, hunger and wet, pain and cold, squalor and filth, cease to have any deterrent effect whatsoever. Death turns into the commonplace and its usual power to check [unscrupulous] actions vanish. The beauty of war in this respect is that it is so congruous with ordinary human nature, James contends. Ancestral evolution has made us all potential warriors so that the most insignificant individual, when thrown into an army in the field, is weaned from whatever excess of tenderness towards his precious person he may bring with him and may easily develop into a monster of insensibility. Yet, when the military type of self-severity is compared with that of the ascetic saint, we find a world of differences in their spiritual attributes. James here gives us an example:

(92)

“To live and let live,” writes an Austrian officer, “is no device for an army. Contempt for one’s own comrades, for the troops of the enemy and, above all, fierce contempt for one’s own person, are what war demands of everyone. Far better is it for an army to be too savage, too cruel, too barbarous, than to possess too much sentimentality and human reasonableness. If the soldier is to be good for anything as a soldier, he must be exactly the opposite of a reasoning and thinking man. War, and even peace, require of the soldier absolutely peculiar standards of morality. The recruit brings with him common moral notions of which he must immediately seek to get rid of. For him, victory, success, must be everything. The most barbaric tendencies in men again come to life in war, and for war’s uses they are incommensurably good.”

The fact is, James professes, that war is a school of strenuous life and heroism; and, being in the line of the savage instinct, it is the only school that, as of yet, is universally available. Therefore, when we gravely ask ourselves whether this wholesale organization of irrationality and crime be our only bulwark against effeminacy, we stand aghast at the thought and think more kindly of ascetic religion.

L.T. – What’s wrong with effeminacy? I think we should somehow infuse estrogen into the brutes’ bodies at the very first signs of their chest-thumping and war bellowing.

Poverty, James suggests, is the strenuous life – without the brass bands or uniforms or hysterical popular applause.

L.T. – Next, wipe out their bank accounts leaving them to sleep in sleeping bags in tents in the park and stand in soup kitchen lines; just as they would in the military. Once the estrogen kicks in, believe me, they will want nothing to do with sleeping outside on the ground in the cold and will soon become sensible and act civilized.

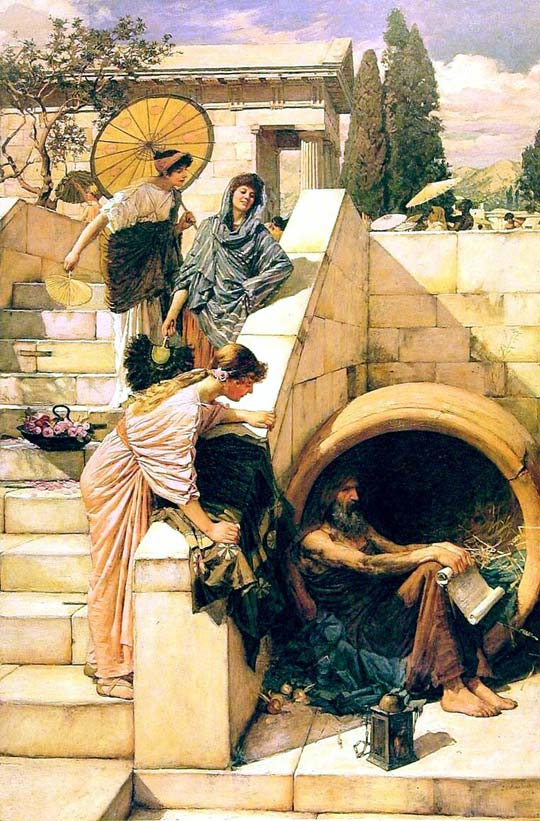

James continues, we despise anyone one who elects to be poor in order to simplify and save his inner life. If he does not join in on the general scramble and pant along money-making street, we deem him spiritless and lacking in ambition. We have lost the power even of imagining what the ancient idealization of poverty meant: the liberation from material attachments, the unbribed soul, the manlier indifference, the paying of our way by what we are or what we do rather than by what we have.

“Diogenes” painted in 1882 by John William Waterhouse (1849- 1917) – one of the greatest artists who ever lived.

Diogenes [roughly 412 – 323 BC] was a Greek philosopher and one of the founders of the Cynic philosophy. He made a virtue of poverty begging for a living and often slept in a large ceramic jar in the marketplace. He became notorious for his philosophical stunts, such as carrying a lamp during the day, claiming to be looking for an honest man.

(93)

It is true, that so far as wealth gives time for ideal ends and exercise to ideal energies, wealth is better than poverty and ought to be chosen. But, wealth does this in only a portion of the actual cases. Elsewhere the desire to gain wealth and the fear of losing it are our chief breeders of cowardice and propagators of corruption. There are thousands of ways in which a wealth bound man must be a slave whilst a man for whom poverty has no terrors becomes a free man. Think of the strength which personal indifference to poverty would give us if we were devoted to unpopular causes. We need no longer hold our tongues for fear of economic consequences (loss of job, promotion, stocks tumble, club doors shut in our faces). Yet, while we lived, we would imperturbably bear witness to the spirit and our example would help to set free our generation. Causes, of course, need funding but as its servants, we would be potent in proportion [perhaps far more so] to any opposing well financed opposition.

L.T. – Due to the above paragraph and my remarks about brutes and their hormonal imbalances that could easily be remedied by giving them estrogen supplements I am here inspired to further inform of the circumstances I found myself in involving organized crime:

After the therapist had convinced me that the mafia was not going to murder me I was initially, albeit briefly, greatly relieved, almost ecstatic. (see Chapter (F) page 27, regarding having purchased a gun to kill myself believing it was the least worst of two dire outcomes). This was then followed by a state of severe depression. Nearly catatonic, I would spend whole days just sitting on the couch staring into space for, even though I had not shot myself, I was still in the same dire situation. My property had been on the market for some time and I rarely, if at all, heard from the real estate agent. The ‘For Sale’ sign posted outside the building was regularly vandalized. On several nights I could hear one of my neighbors repeatedly kicking the metal sign; it was very loud. I knew it was my neighbor because I could hear his voice as well. Perhaps four days or so after the gun incident, I received a letter from a real estate agent, whom I knew not and had never contacted. I deduced that this letter did not come at this time by chance alone. Regardless, I wanted out of the property and telephoned the realtor who sent the letter and we made an appointment for an early evening visit a few days hence. He did not show up and I figured it was just more of the same sort of ‘jerking me around’ that I had been, at this point, used to experiencing, and I did not expect I would at all meet with the realtor. However, he showed up unexpectedly early the next morning. Once I had invited him inside the studio he made a comment regarding my early morning appearance.

(94)

I could tell right away that he was a member of, or affiliated somehow, with this criminal organization. (You get so you recognize many of them fairly quickly – they sometimes, not always, possess similar subtle characteristics). During our first meeting that morning he told me that the previous realtor was too frightened to work with the property. He also stated that my neighbors were mafia. He casually mentioned that, “A good friend is someone who will help you bury a body,” and asked me out for a date. I desperately wanted out of the neighborhood, out of the condominium, and I wanted to live, so I agreed to go out with him and signed his real estate sales contract.

During our first date, over dinner, he told me of a community he lived in outside of Chicago that was a community of recreational, private airplane pilots. The community had a small runway and hangers to park the home owners’ airplanes in. He mentioned that he sold a neighbor, a doctor, a parachute of his. Later, as the doctor was flying, his plane malfunctioned and he had to eject himself from the airplane. The realtor then told me that the first parachute did not release and the second backup parachute had a tear in a seam resulting in the doctor plummeting to the ground and to his death. He then stated that the doctor was an a$$hole.

On another occasion, during a time when he was grieving over having to put his dog to sleep, I asked him if he planned on getting another pet. He said, “No, I’m tired of putting people down.” That was a slip of the tongue, I assumed, but with some truth to it. On another day when he took me to a commercial gold mining property for a hike, and just after we parked but had not yet gotten out of the car, I asked him if he was going to kill me (meaning out in the wilderness). I wasn’t hysterical at all, I had come to expect to be killed at some point and began to feel an ongoing malaise about it. He responded, “I would not hurt a hair on your head.” After hiking a bit and stopping for lunch he pulled out a knife, with about a seven inch long blade, and went on describing in detail its sharpness. The realtor then told of a scene in the movie “Ryan’s Song,” a war movie where, as a German soldier in hand-to-hand combat with an American soldier was sinking a knife into the chest of the American, the German was saying “There, you go to sleep now.” The realtor said, even when one is killing another the killer can feel compassion for his victim.

There’s more, much more, I could report, including drugging (I believe he was slipping antidepressants into my bottled drinking water) and a certain and specific incident of hypnosis. Also, I was sexually entertaining him to stay alive. Eventually, another realtor from another firm altogether managed to sell my condominium and get me out of that dreadful neighborhood.

This is the part that is quite shocking. This realtor told me he knew my ex-husband’s attorney (I never told the realtor who my husband’s attorney was) and that he was good friends with her and her husband who was a home builder. And, that he had, as one of his real estate listings, a very expensive home that the attorney’s husband had built on spec. He also told me of a female that the attorney had introduced him to as a possible romantic connection (here underscoring that the real estate agent and the attorney were good friends). On one occasion he told me not to contact my ex-husband for he was under extreme stress and not at all well. Adam’s circumstances were as stressful as mine, maybe more so but, I would rather not, for his and his new family’s sake, go into detail here. I should add however, that our divorce was not contentious and for a while, early on, Adam helped me out a good deal. The realtor’s comment cost me several nights’ sleep worrying that Adam too was being menaced as I was by these thugs. I then deduced (wrongly unfortunately) that the realtor was just being manipulative and decided that Adam was probably fine. Obviously my ex-husband’s attorney had stepped outside proper, perhaps legal even, bounds of professional conduct. I suspect that it was she who sent him in my direction initially. She is now a judge.

This has all been officially reported. Back to the book:

*Update: Presently, several years later, two of the offices where many of these people operated from are closed down.

(95)

James concludes that whoever possesses strongly a sense of the divine, instead of placing happiness where common men place it (in comfort) the saintly places it in a higher kind of inner excitement which converts discomforts into sources of cheer thus annulling unhappiness. He turns his back upon no duty, however thankless, and when we are in need of assistance we can count upon the saint lending his hand with more certainty than we can count upon any other person. Finally, his humble-mindedness and his ascetic tendencies save him from the petty personal pretensions which so obstruct our ordinary social intercourse and, his purity gives us in him a clean man for a companion. Exhilaration, purity, charity, patience, self-severity – these are splendid excellencies and the saint, above all men, shows them in the most completely possible measure.

But, as we have seen, all these things together do not make saints infallible. When their intellectual outlook is narrow, they fall into all sorts of holy excesses, fanaticism or theopathic absorption, self-torment, prudery, scrupulosity, gullibility and a morbid inability to meet the world. In fact, says James, in some circumstances a saint can be even more objectionable and damnable than the superficial carnal man. Therefore we must judge him not sentimentally only, and not in isolation, but using our own intellectual standards when estimating his total function. James states that the most inimical critic of the saintly impulses whom he knows of is Friedrich Nietzsche. He contrasts the saints with the worldly; such as we find them embodied in the predaceous military character, and to the advantage of the latter.

In fact, says James, the saint does appeal to a different faculty as enacted in the fable about the wind, the sun, and the traveler.

L.T. – Which here I shall include:

The 6th century B.C. Aesop Fable “The Wind and the Sun”

The Wind and the Sun were disputing which was the stronger. Suddenly, they saw a traveler coming down the road and the Sun said, “I see a way to decide our dispute. Whichever of us can cause that traveler to take off his cloak shall be regarded as the stronger.” “You go first,” the Sun said to the Wind then retired behind a cloud and the Wind began to blow as hard as it could upon the traveler. But, the harder he blew the more closely did the traveler wrap his cloak around him until, at last, the Wind had to give up. Then, the Sun came out and shone in all his glory upon the traveler who soon found it too hot to walk with his cloak on. Moral of the story: Kindness affects more than severity.

(96)

James continues: For Nietzsche, the saint represents little more than slavishness and his prevalence would put humankind in danger. Here the author quotes Nietzsche [much abridged]:

“The sick are the greatest danger for the well. The weaker, not the stronger, are the strong’s undoing. The morbid are our greatest peril – not the bad men, not the predatory beings. Those born wrong, the miscarried, the broken – those who are the weakest are undermining the vitality of the race, poisoning our trust in life and putting humanity in question. And here swarm the worms of sensitiveness; here is woven endlessly the net of the meanest of conspiracies: the conspiracy of those who suffer against those who succeed and are victorious. For them [the saintly conspirators] the very aspect of the victorious is hated as if health, success, strength and pride and the sense of power were in themselves things vicious and for which one ought to make bitter expiation [atonement].”

Poor Nietzsche’s antipathy is itself sickly enough laments James. Yet, he well expresses the clash between the two ideals: The carnivorous-minded strongman, the adult and cannibal male who can see nothing but mouldiness and morbidness in the saint’s gentleness and self-severity and regards him with pure loathing. The whole feud essentially revolves upon two pivots: Shall the seen world, or the unseen world, be our chief sphere of adaptation? And in the seen, the empirical world, must our means of adaptation be aggressiveness or non-resistance? The debate is serious, James insists, and both worlds must be taken into account.

![220px-Nietzsche187a[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/220px-Nietzsche187a1.jpg) Frederik Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) was a German philosopher who challenged the foundations of Christianity and traditional morality.

Frederik Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) was a German philosopher who challenged the foundations of Christianity and traditional morality.

In all fairness, I need to add here: After Nietzsche’s death, his sister, Forster-Nietzsche, became the curator and editor of her brother’s manuscripts. She reworked his unpublished writings to fit her own German nationalist ideology while often contradicting or obfuscating his stated opinions which were opposed to antisemitism and nationalism. And, through these publications, Nietzsche’s name became associated with fascism and Nazism.

James alleges that a certain kind of man must be the best kind of man – absolutely apart from the utility of his function [his work]; apart from economic considerations. The saint’s type, and the knight’s or gentleman’s type, have always been rival claimants to the title of the ideal man. And, in the regimented religious orders, both types blend, in a sense.

A society where all are aggressive would destroy itself; some must be non-resistant if there is to be any kind of order. However, the aggressive members tend to become bullies, robbers and swindlers. Meanwhile, it is possible to conceive of an imaginary society in which there would be no aggressiveness; only sympathy and fairness. To such a society the saint would be entirely adaptive whereas the strong man would immediately tend, by his presence, to make that society deteriorate. It would eventually become inferior in everything while adding a certain kind of bellicose excitement; so dear to men as they are today.

(97)

Yet, there is no absoluteness in the excellence of sainthood. Here James adds as a footnote: We all know of daft saints, and they inspire a queer kind of aversion. But, in comparing saints with strong men we must choose individuals on the same intellectual level. The under-witted strong man (homologous in his sphere with the under-witted saint) is the bully of the slums, the hooligan or rowdy. So surely, on this level too, the saint can claim a certain superiority.

James here asserts that in our western world religion has seldom been so radical that the devotee could not mix it [the religion] with some worldly temper; always finding good men to follow, but stopping short when it comes to outright non-resistance. Christ himself was fierce upon occasion.

How then is success to be measured absolutely when there are so many environments and so many ways of looking at the adaptation [or of the teaching by example]? It cannot. The verdict will vary according to the point of view. From the physiological point of view, Saint Paul was a failure because he was brutally executed. Yet, he was magnificently adapted to the larger environment of history; he is a success no matter what his immediate bad fortune may have been. The greatest saints, the spiritual heroes whom everyone acknowledges, are successes from the outset. They show themselves and there is no question that everyone perceives their strength and stature. Their sense of the mystery in things, their passion, their goodness, irradiate about them and enlarge, and soften, their outlines.

Economically speaking, the qualities of the saintly are indispensable to the world’s welfare. The great saints are immediate successes and the smaller ones are, at least, heralds and harbingers of a better order, posits James. Let us be saints then, if we can, whether or not we succeed visibly and temporally. For, in our Father’s house there are many mansions and each of us must discover for ourselves the best kind of religion and the amount of saintsmenship which best comports with what one believes to be within their power and, their truest mission and vocation.

L.T. – As the author, William James, here has done.

How, you ask, can religion, which believes in two worlds and an invisible order, be estimated by the adaption of its fruits to this world’s order? It is its truth, not its utility, upon which our verdict ought to depend, James replies. If religion is true, its fruits are good fruits, even though in this world they should prove uniformly ill adapted and full of nothing but pathos.

Now, the plot thickens: Religious persons have often, though not uniformly, professed to see truth in a special manner. That manner is known as mysticism.

(98)

Lectures XVI and XVII – MYSTICISM

James begins this section reminding us that over and over again he has raised points and left them unfinished until we should arrive at the subject of Mysticism. And now the hour has come, he writes, when mysticism must be faced in good earnest. For, he feels, personal religious experience has its origin and center in mystical states of consciousness. James also informs us that his personal constitution shuts him out from their enjoyment and that he can only speak of them second hand. Though, he assures us, being forced to look upon the subject externally, he will be as objective and receptive as possible and believes he will, at least, succeed in convincing the reader of the reality of the states in question and of their paramount importance.

The words “mysticism” and “mystical” are often used as terms of mere reproach; to generally throw at any opinion which is regarded as too vague, vast and sentimental, and without basis in facts or logic. So, to keep it useful by restricting it, James advises that he will do what he did in the case of the word “religion” and simply propose to the reader four qualities which, when experienced, may justify our calling it a mystical experience:

Ineffability – The subject of the mystical experience defies linguistic expression; that no adequate report of its contents can be given in words. It follows from this that its quality must be personally experienced; it cannot be imparted or transferred to others. Given this peculiarity, mystical states are more like feeling states than like states of the intellect. For example, one must have musical ears to know the value of a symphony [the same is true, and quite obviously so to me as artist, about the visual arts]; one must have been in love one’s self to understand a lover’s state of mind. Lacking the heart, or ear, [or eye] we cannot interpret the musician, the artist, or the lover justly and are even likely to consider them weak. The mystic finds that most people accord to their experiences an equally incompetent treatment.

Noetic quality – Mystical states seem to those who experience them to be states of knowledge. They are illuminations, revelations, full of significance and importance.

Transiency – Mystical states cannot be sustained for long. Except in rare instances, half an hour to an hour or two, at most, seems to be the limit beyond which they fade into the common light of day.

Passivity – The oncoming of mystical states may be facilitated by preliminary voluntary operations (for example: fixing the attention, going through certain bodily performances, or in other ways in which manuals of mysticism prescribe). Yet, when the characteristic sort of [mystical] consciousness has set in, the mystic feels as if his own will were in abeyance. And indeed, sometimes it is as if he were grasped and held by a superior power; as in the case of the phenomena of secondary or alternative personality such as prophetic speech, automatic writing or mediumistic trance. However, there may be no recollection whatsoever of these particular phenomena by the subject. And, it may not be of significance specifically to the subject’s own inner life to which, as it were, it makes a mere interruption. Mystical states, strictly so called, are never merely interruptive. Some memory of their content always remains, along with a sense of their importance, and they tend to modify the inner life of the subject. Sharp divisions in this region are difficult to make however, and we find all sorts of gradation and mixtures.

These four characteristics are sufficient to mark out a group of states of consciousness extraordinary enough to deserve a special name and to call for careful study: the mystical group.

(99)

James here states, as he did in his first lecture, that phenomena are best understood when placed within their series, studied in their germ and in their over-ripe decay and, compared with their exaggerated and degenerated kindred. The method of serial study is essential for interpretation if we really wish to reach conclusions. Thus he shall begin with phenomena which claim no special religious significance and end with those of which the religious pretensions are extreme.

Most of us know of the strangely moving power of passages in certain poems, says James. Lyrical poetry and music are alive and significant in equal proportion as they fetch vague vistas of a life continuous with a particular age, beckoning and inviting us. James avows that we are either alive or dead to the eternal messages of the arts according to whether or not we have, generally, kept since our youth this mystical susceptibility.

Here the author asks us to consider on the mystical ladder an extremely common phenomenon: that sudden feeling which sweeps over us of having “been there before” as if at some indefinite time in the past, in just this place, with just these people, we were already saying these things. As the poet, Tennyson, writes:

“Moreover, something is or seems; That touches me with mystic gleams; Like glimpses of forgotten dreams – “

“Of something felt, like something here; Of something done, I know not where; Such as no language may declare.”

Lord Alfred Tennyson (1809 – 1892) was Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland during Queen Victoria’s reign and is, to this day, one of the most popular British poets. “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and “In Memoriam A.H.H.,” written to commemorate his friend Arthur Hallan, a fellow poet and student at Trinity College, Cambridge, after he died of a stroke just 22 years of age, are among his most well-known works. Queen Victoria had wrote in her diary that she was “much soothed and pleased” by reading “In Memoriam A.H.H.” following the death of her beloved husband, Prince Albert. It is in that poem the phrase “Tis better to have loved and lost; Than to never have love at all” is written. Other well-known phrases by Tennyson are, “Theirs is not to reason why; Theirs is but to do and die,” and “Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers.” Source – Wikipedia

Lord Alfred Tennyson (1809 – 1892) was Poet Laureate of Great Britain and Ireland during Queen Victoria’s reign and is, to this day, one of the most popular British poets. “The Charge of the Light Brigade” and “In Memoriam A.H.H.,” written to commemorate his friend Arthur Hallan, a fellow poet and student at Trinity College, Cambridge, after he died of a stroke just 22 years of age, are among his most well-known works. Queen Victoria had wrote in her diary that she was “much soothed and pleased” by reading “In Memoriam A.H.H.” following the death of her beloved husband, Prince Albert. It is in that poem the phrase “Tis better to have loved and lost; Than to never have love at all” is written. Other well-known phrases by Tennyson are, “Theirs is not to reason why; Theirs is but to do and die,” and “Knowledge comes, but Wisdom lingers.” Source – Wikipedia

L.T. – his part of the book is rather curious, a synchronicity actuality, for I had just (but two days ago and prior to reading this chapter on Mysticism) included on chapter (C) MIRACLES “Thanksgiving and a Birthday” a poem I had written for Chad for his birthday and with it, an account of a synchronicity involving the poet E.E. Cummings. I had mentioned to him that poetry comes from an entirely different area of thought and expression than other sorts of mental activities and this can literally be felt when writing poetry. I also stated that it is as though once I start in on a poem, it seems to write itself and that, in general, poetry’s wondrous depth of feeling comes, not only from the words but, from the rhyme and the rhythm of the verses, like music. I then went on about music (symphonic music in particular) explaining that, once having learned how to play the piano and flute (I do not profess to be accomplished in either) I have a far greater expanse of understanding, and therefore enjoyment of, music than I would have had I never learned to play an instrument. In regards to many great musical compositions, I am in a state of awe realizing all that goes into their creation and production. This project, this discovery and writing of James’ book, is the happiest project I have ever undertaken. I feel as if I have found my “kind,” so to speak; people like myself, whom I’ve never before encountered, known or known of. Also, I have been experiencing since I began this project a couple of months ago (as of this writing) synchronistic, miraculous events, almost daily.

(100)

In a footnote James adds: Tennyson writes to a friend, “I have never had any revelations through anesthetics of any kind, but a walking trance, for lack of a better word, I have frequently experienced since boyhood, when I have been all alone. This has come upon me through repeating my own name to myself silently, till all at once, as it were, out of the intensity of the consciousness of individuality, individuality itself seemed to dissolve and fade away into boundless being. And, this is not a confused state but the clearest, the surest of the surest, utterly beyond words state – where death was an almost laughable impossibility – the loss of personality seeming not extinction, but the only true life. I am ashamed of my feeble description. Have I not said the state is utterly beyond words?”

A much more extreme state of mystical consciousness is described by J. A. Symonds and, James believes, that probably more persons than we suspect could give parallels to it from their own experience [much abridged]:

“Suddenly at church, or in company when I was reading, and always, I think, when my muscles were at rest, I felt the approach of the mood. Irresistibly it took possession of my will and mind and lasted for what seemed an eternity …” “It consisted in a gradual but swiftly progressive obliteration of space, time, sensation, and the multitudinous factors of experience which seem to qualify what we are pleased to call our Self. But, Self persisted, formidable in its vivid keenness.” Symonds continues, “This trance recurred with diminished frequency until I reached the age of twenty-eight. Often I have asked myself with anguish, on waking from that formless state of denuded, yet keenly sentient being, which is the unreality – the trance of fiery, vacant, apprehensive, skeptical Self from which I issue [here described], or these surrounding [ordinary] phenomena and habits which veil that inner Self and build a self of flesh and blood? Are men the factors of some dream, the dream-like insubstantiality of which they comprehend at such eventful moments?”

Symonds writes of another mystical, perhaps, experience he had only this time under the influence of chloroform [so very much like the many accounts of the near death experiences we have today been told of]:

“After the choking and stifling had passed away, I seemed at first in a state of utter blankness. Then came flashes of intense light, alternating with blackness, and a keen vision of what was going on in the room around me, but no sensation of touch. I thought that I was near death; when suddenly my soul became aware of God who was manifestly dealing with me, handling me, so-to-speak, in an intense personal present reality. I felt him streaming in like light upon me. I cannot describe the ecstasy I felt. Then, as I gradually awoke from the influence of the anesthetics, the old sense of my relation to the world began to return while the new sense of my relation to God began to fade. I suddenly lept to my feet and shrieked out, ‘It is too horrible, it is too horrible!‘ meaning that I could not bear this disillusionment. Then I flung myself on the ground and, at last awoke covered with blood, calling to the two surgeons (who were frightened) “Why did you not kill me?” To have felt for that long timelessness, the ecstasy of the vision of God in all purity and tenderness and truth and absolute love, and then to find that I had, after all, no revelation but that I had been tricked instead by the abnormal excitement of my brain.”

(101)

“Yet,” continues Symonds, “this question remains, is it possible that when my flesh was dead to the ordinary sense of physical relations to impressions from without, that the inner sense of reality which then succeeded, was not a delusion but an actual experience? Is it possible that I, in that moment, felt what some of the saints have said they always felt, the indemonstrable but irrefutable certainty of God?”

Here James addresses another type of anesthetic state: Nitrous oxide, when sufficiently diluted with air, stimulates the mystical consciousness to an extraordinary degree. Depth beyond depth of truth seems revealed to the inhaler. This truth fades out, however, or escapes, at the moment of coming to; and if any words remain, they prove to be complete nonsense. Nonetheless, the sense of a profound meaning having been there persists. And James claims to have known more than one person who is persuaded that in the nitrous oxide trance we have the genuine metaphysical revelation.

The author confesses that he personally made some observations on this aspect of nitrous oxide intoxication and reported of them in print. And, this impression of its truth has ever since remained unshaken: that being, our normal waking, rational consciousness is but one special type of consciousness. While all about it [ordinary consciousness], and parted from it by the filmiest of screens, there lie potential forms of entirely different consciousness’. He adds that we may go through life without suspecting their existence; but apply the requisite stimulus and, at a touch, they are there. How to regard them is the question – for, they are so discontinuous with ordinary consciousness. James goes on to say that looking back on his own experiences, they all converge towards a kind of insight to which he cannot help but ascribe some metaphysical significance: It is as if the opposites of the world, whose contradictoriness and conflict make all our difficulties and troubles, were melted into unity. Not only do they, as contrasted species, belong to one and the same genus, but one of the species, the nobler and better one, is itself the genus, and so soaks up and absorbs its opposite into itself.

L.T. – As I have already done previously in this work, I will again refer the reader to an experience of mine that James has so perfectly just described: chapter (A) Divine Message, Enlightenment, ESP, etc. in the section titled: Seeing continued – The Holy Instant, Samadhi, or Enlightenment [link below]. For, I wish to make it clear that this experience, and the several others I have had that are of a mystical or paranormal nature, were never associated with drugs of any kind. At the same time, by making this statement I do not here intend to at all suggest that if someone is convinced that they have had a metaphysical experience while under the influence of a drug of some type that their experience was not genuinely metaphysical. I am merely stating that my experiences have never occurred while under the influence of drugs.

Link: https://miraclesforall.com/miracle-stories-page1/

(102)

Here the author includes a passage by Xenos Clark (a philosopher who died young, in the 1880’s, much lamented by those who knew him) from the book “The Anesthetic Revelation and the Gist of Philosophy” by Benjamin Paul Blood published in New York, 1874 [much abridged]:

“The truth is that we travel on a journey that was accomplished before we set out; and the real end of philosophy is accomplished, not when we arrive at, but when we remain in our destination (being there already) which may occur vicariously in this life when we cease our intellectual questioning. That is why there is a smile upon the face of the revelation, as we view it. It tells us that we are forever half a second too late – that’s all. You could kiss your own lips, it says, if you only knew the trick. It would be perfectly easy if they [your lips] would just stay there till you got around to them.”

Clark continues, “Repetition of the experience finds it ever the same. The subject resumes his normal consciousness only to partially and fitfully remember its occurrence, and to try to formulate its baffling importance with only this consolatory afterthought: that he has always known the oldest truth, and that he is done with human theories as to the origin, meaning, or destiny of the race. For, he is beyond instruction in spiritual things. The lesson is one of central safety: the Kingdom is within. All days are judgment days; there can be no climatic purpose of eternity, nor any scheme of the whole. The astronomer abridges the row of bewildering figures by increasing his unit of measurement; that we may then reduce the distracting multiplicity of things to the unity for which, each one of us stands.”

James then cites an account from a correspondence from a Mr. Trine: “I know of an officer on our police force who has told me that many times, when off duty and on his way home in the evening, there comes to him such a vivid and vital realization of his oneness with this Infinite Power. This Spirit Of Infinite Peace so takes hold of and so fills him that it seems as if his feet could hardly keep to the pavement, so buoyant and so exhilarated does he become by reason of the inflowing tide.”

Certain aspects of nature, James informs us, seem to have a peculiar power of awakening such mystical moods. Here he includes a case from Professor Starbuck’s collection [quite abridged]:

“… in that time the consciousness of God’s nearness came to me sometimes. I say ‘God’ to describe what is indescribable. A presence, I might say, yet that is too suggestive of a personality. Yet, the moments of which I speak did not hold the consciousness of a personality but, something in myself made me feel myself as part of something bigger than I and, was controlling. I felt myself one with the grass, the trees, birds, insects, everything in Nature. I rejoiced in the mere fact of existence, of being a part of it all – the drizzling rain, the shadows of the clouds, the tree trunks, and so on. In the years following, such moments continued to come but I wanted them constantly for, I knew so well the satisfaction of losing self in a perception of supreme power and love that I was unhappy because that perception was not constant.”

(103)

James says he could easily give more instances of cases he has collected that occurred out of doors and includes one more in his book but, for the sake of brevity and making room for a more interesting case, we’ll move on. The author now tells us of a Canadian psychiatrist, Dr. R. M. Bucke who gives to the more distinctly characterized of these phenomena the name of “cosmic consciousness” defined by Dr. Bucke as such:

“Cosmic consciousness is a consciousness of the cosmos that is of the life and order of the universe. Along with the consciousness of the cosmos there occurs an intellectual enlightenment which alone would place the individual on a new plane of existence – would make him almost a member of a new species. To this is added an indescribable feeling of elevation and joyousness and a quickening of the moral sense which is fully as striking as, and more important than, the enhancement of the intellectual power.”

James informs us that it was Dr. Bucke’s own experience of a typical onset of cosmic consciousness in his own person which led him to investigate it in others. From Bucke’s book “Cosmic Consciousness – a study in the evolution of the human mind” Philadelphia, 1901:

“I had spent the evening in a great city, with two friends reading and discussing poetry and philosophy. We parted at midnight and I had a long drive to my lodging. My mind was deeply under the influence of the ideas, images, and emotions called up by the reading and talk. I was calm and peaceful; letting ideas, images and emotions flow in and of themselves, as it were, through my mind. All at once, without warning of any kind, I found myself wrapped in a flame colored conflagration from somewhere close by in the great city. Then next, I knew that the fire was not outside me but rather within me. What suddenly followed was a sense of exultation, of immense joyousness immediately followed by an intellectual illumination impossible to describe. I did not merely come to believe, among other things, but saw that the universe is not composed of dead matter; on the contrary, a living Presence. I became conscious in myself of eternal life; meaning not that I would have, but that I was, eternal life. I saw that all men are immortal and that the cosmic order is such that, without any doubt, all things work together for the good of each and all and that the founding principle of this world, of all worlds, is what we call love. And, that the happiness of each and all is, in the long run, certain. The vision lasted but a few seconds and was gone. But, the memory of it and the sense of the reality of what it taught me has remained during the quarter of a century which has since elapsed; I knew that what the vision showed me was true. That view, that conviction, that consciousness, has never, even during periods of the deepest depression, been lost.”

(104)

Here, in a footnote, James gives us a quote from “Vivekananda” by Raja Yoga, London, 1896:

“The mind itself has a higher state of existence, beyond reason, a superconscious state. And, when the mind gets to the higher state, then knowledge beyond reasoning comes.”

Before we start in on this next part of James’ book I think it is a good idea to define a few of the religious terms he uses:

Samadhi – [Hinduism and Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism and yogic schools] a state of meditative consciousness attained by the practice of dhyana. In Hindu yoga this is regarded as the final stage, at which union with the divine is reached (before or at death); a state of meditative consciousness sometimes attained by the practice of dhyana.

Dhyana [Hinduism] – meditation which is a deeper awareness of oneness which is inclusive of perception of body, mind, senses and surroundings, yet remaining unidentified with them and leads to Samadhi and self-knowledge. [Buddhism] – a series of cultivated states of mind which lead to perfect equanimity and awareness.

Vedanta – one of the six orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy. The term Veda means “knowledge” and anta means “end” originally referred to in the Upanishads; a collection of foundational texts in Hinduism.

Sufism – according to its adherents, is the inner mystical dimension of Islam. Practitioners of Sufism, referred to as Sufis, belong to a congregation formed around a grand master referred to as a Mawla who maintains a direct lineage of teachers dating back to the Prophet Muhammad. Sufis strive for ishan (perfection of worship) as detailed in a hadith (Arabic for narrative – in this case a collection of reports claiming to quote what the Prophet Muhammad said verbatim on any matter). Sufis regard the Prophet Muhammad as the primary perfect man who exemplifies the morality of God and their leader and prime spiritual guide. Sufis consider themselves to be the true proponents of the pure, original form of Islam.

Nirvana – [Buddhism] freedom from the endless cycle of personal reincarnations. The final beatitude that transcends suffering, karma, and samsara [in Hinduism – the endless cycle of births, deaths, and rebirths] and is sought through the extinction of desire and individual consciousness.

(105)

Now back to James’ book:

The Hindu Vedantists say that one may stumble into super-consciousness sporadically, without the previous discipline, but it is then impure. Their test of its purity, like our test of religion’s value, is empirical: its fruits must be good for life. When a man comes out of Samadhi, he remains enlightened, a sage, a prophet, a saint; his whole life is changed, illumined.

The Buddhists, James explains, used the word “samadhi” as well as the Hindus; but “dhyana” is their special word for higher states of contemplation. There seems to be four stages recognized in dhyana [in Buddhism]. The first stage comes through concentration of the mind upon one ![Phra_Ajan_Jerapunyo-Abbot_of_Watkungtaphao[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Phra_Ajan_Jerapunyo-Abbot_of_Watkungtaphao1-225x300.jpg) point. It excludes desire, but not discernment or judgment; it is still intellectual. In the second stage, the intellectual functions drop off, and the satisfied sense of unity is felt. In the third stage, the satisfaction departs and indifference begins along with memory and self-consciousness. In the fourth stage, the indifference, memory and self-consciousness are perfected. James here states that just what memory and self-consciousness mean in this connection cannot be the same faculties familiar to us in the lower life. Higher stages still of contemplation are mentioned – a region where nothing exists and where the meditator says: “There exists absolutely nothing” and stops. He then reaches another region where he says: “There are neither ideas nor absence of ideas,” and again stops. Then another region where, “having reached the end of both idea and perception, he stops finally.” This would seem to be, not Nirvana, but as close an approach to it as this life affords.

point. It excludes desire, but not discernment or judgment; it is still intellectual. In the second stage, the intellectual functions drop off, and the satisfied sense of unity is felt. In the third stage, the satisfaction departs and indifference begins along with memory and self-consciousness. In the fourth stage, the indifference, memory and self-consciousness are perfected. James here states that just what memory and self-consciousness mean in this connection cannot be the same faculties familiar to us in the lower life. Higher stages still of contemplation are mentioned – a region where nothing exists and where the meditator says: “There exists absolutely nothing” and stops. He then reaches another region where he says: “There are neither ideas nor absence of ideas,” and again stops. Then another region where, “having reached the end of both idea and perception, he stops finally.” This would seem to be, not Nirvana, but as close an approach to it as this life affords.

In The Mohammedan world, the Sufi sect and various dervish [see image of whirling dervishes] bodies are the possessors of the mystical tradition. The Sufis have existed in Persia since the earliest times. And, as their pantheism is so at variance with the hot and rigid monotheism of the Arab mind, it has been suggested that Sufism must have been introduced into Islam by Hindu influences. James tells us that we Christians know little of Sufism for, its secrets are disclosed only to those initiated. But, to give its existence a certain liveliness in our minds James quotes a Moslem philosopher and theologian, Al-Ghazzali, a Persian from the eleventh century who ranks as one of the greatest theologians of the Moslem church [much abridged]:

In The Mohammedan world, the Sufi sect and various dervish [see image of whirling dervishes] bodies are the possessors of the mystical tradition. The Sufis have existed in Persia since the earliest times. And, as their pantheism is so at variance with the hot and rigid monotheism of the Arab mind, it has been suggested that Sufism must have been introduced into Islam by Hindu influences. James tells us that we Christians know little of Sufism for, its secrets are disclosed only to those initiated. But, to give its existence a certain liveliness in our minds James quotes a Moslem philosopher and theologian, Al-Ghazzali, a Persian from the eleventh century who ranks as one of the greatest theologians of the Moslem church [much abridged]:

“The science of the Sufis aims at detaching the heart from all that is not God and giving it up for the sole occupation of the divine being.” “… my heart no longer felt any difficulty in renouncing glory, wealth, and my children” says Al-Ghazzali, “so I quitted Bagdad and, reserving from my fortune only what was indispensable for my subsistence, and I distributed the rest. I went to Syria, where I remained about two years with no other occupation than living in retreat and solitude conquering my desires, combating my passions, training myself to purify my soul, to make my character perfect, to prepare my heart for meditating on God – all according to the methods of the Sufis, as I had read of them.”

“I recognized, for certain, that the Sufis are assuredly walking in the path of God. Both in their acts and in their inaction, whether internal or external, they are illumined by the light which proceeds from the prophetic source. The first condition for a Sufi is to purge his heart entirely of all that is not God. The next key to the contemplative life consists in the humble prayers which escape from the fervent soul and, in the meditation of God in which the heart is swallowed up entirely. But, in reality this is only the beginning of the Sufi life; the end of Sufism being total absorption in God.” “… revelations take place in so flagrant a shape that the Sufi’s see before them, whilst wide awake, the angels and the souls of the prophets. They hear their voices and obtain their favors.”

Al-Ghazzali goes on to describe the prophetic faculty as being analogous to such: “… sleep. If you were to tell a man who has never had the [sleep] experience that there are people who at times swoon away so as to resemble dead men, and who [in dreams] perceive things that are hidden [from the outside observer], he would deny it. Nevertheless, his arguments would be refuted by actual experience. Just so, in the prophetic, the sight is illumined by a light which uncovers hidden things and objects which the intellect fails to reach. The chief properties of prophetism are perceptible only during the transport, and by those who embrace the Sufi life.”

(106)

James posits that it is a commonplace of metaphysics that God’s knowledge cannot be discursive but must be intuitive; that is, it must be constructed more after the pattern of what in ourselves is called immediate feeling than after that of proposition and judgment [faculties of the intellect]. But, James asserts, our immediate feelings have no content beyond what the five senses supply. Yet, we have seen and shall see again that the mystics may emphatically deny that the senses play any part in the very highest type of knowledge which their transports yield.

In the Christian church there have always been mystics. The experiences of these mystics have been treated as important precedents and the church has codified a system of mystical theology based upon them. “Orison,” or meditation, is the groundwork for the methodical elevation of the soul towards God. And, it is through continued practice of orison the higher levels of mystical experience may be attained. It is odd however, James notes, that Protestantism, especially evangelical Protestantism, should seemingly have abandoned everything methodical in this line apart from what prayer might lead to.

The first thing to be aimed at in orison is the mind’s detachment from outer sensations for, these interfere with its concentration upon ideal things. Such manuals as “Saint Ignatius’s Spiritual Exercises” recommend the discipline to expel sensation by a graduated series of efforts including imagined holy scenes. For example, an imaginary figure of Christ coming fully to occupy the mind. But, in certain cases imagery may fall away entirely and in the very highest raptures it tends to do so.

As you may recall, James, in a previous chapter, wrote not all that favorably about Saint Teresa. However, here he includes quite a few passages of her mystical experiences from her autobiography [much abridged]:

“In the orison of union, the soul is fully awake in regards to God, but wholly asleep in regards to things of the world and in respect to herself. During the short time the union lasts, she is deprived of every feeling and cannot think of a single thing. She needs to employ no artifice in order to arrest [employ] the use of her understanding. For, it remains so stricken in inactivity that she neither knows what she loves, nor in what manner she loves, nor what is that she wills. In short, she is utterly dead to the things of the world, living solely in God.”

(107)

Saint Teresa continues, “Thus does God, when he raises a soul to union with Himself, suspend that natural action of all her faculties. She neither sees, hears, nor understands so long as the union lasts. But, this time is always short, and seems even shorter than it actually is. God establishes himself in the interior of this soul in such a way that when she returns to herself, it is wholly impossible for her to doubt that she has been in God, and God in her. This truth remains so strongly impressed on her that, even though many years should pass without the condition returning, she can neither forget the favor she received, nor doubt its reality.”

L.T. – This last paragraph closely describes my own same experience that I wrote of on chapter (A) MIRACLES in the second account titled “More on Seeing Heaven.” My experience came about quite unexpectedly when I was sixteen years old during a conversation with a friend. I had asked her why she believed in God. I had not been meditating. I didn’t even know what meditation was then. This is all quite surprising to me; that is, to read of so many other’s experiences much like the ones I’ve had. Other individuals’ similar accounts in James’ book use the word “transport,” and in my description of the experience, I refer to the sensation of traveling at a surreal, not at all earthly, rate of speed.

James alleges that the kinds of truth communicable in mystical ways, whether these be sensible or supersensible, are various. Some of them relate to this world. For example: visions of the future, the “reading of hearts” [whereby a Saint is able to read into the heart and conscience of an individual and then be able to guide the person towards a greater union with God], the sudden understanding of texts, and knowledge of distant events. But, the most important revelations are theological or metaphysical.

In a footnote here, James mentions that he omits cases of visual and auditory hallucination, verbal and graphic automatisms [as in automatic writing and channeling] and such marvels as “levitation, stigmatization, and the miraculous healing of disease. These phenomena, which mystics have often demonstrated, have not mystical significance according to the author. For, they occur without any “consciousness of illumination” whatsoever and, they often occur in persons of non-mystical minds. Consciousness of illumination is, for us, the essential mark of mystical states.

(108)

Here he cites such “consciousness of illumination” or mystical revelations as experienced by Saint Ignatius:

“Saint Ignatius confessed one day to Father Laynez that a single hour of meditation had taught him more truths about heavenly things than all the teachings of all the theologians put together. One day, in orison, on the choir steps of the Dominican Church, he saw in a distinct manner the plan of divine wisdom in the creation of the world. On another occasion, during a procession, his spirit was ravished in God, and it was given him to contemplate the deep mystery of the Holy Trinity in a form and with images necessarily fitted to the weak understanding of a dweller on Earth. This last vision flooded his heart with such sweetness that, in later times, the mere memory of it made him shed abundant tears.”

Saint Ignatius of Loyola (1491 – 1556) was a Spanish knight from a Basques noble family, a hermit, a priest and founder of the Society of Jesus; a male religious congregation of the Catholic Church. Members are called Jesuits. Today, the Jesuits are engaged in evangelization and apostolic ministry in 112 nations on six continents. Ignatius became the society’s first Superior General. The society participated in the Counter Reformation (beginning with the Council of Trent in 1545 and ending at the close of the Thirty Year’s War in 1648); a movement whose purpose was to reform the Catholic Church from within and to counter the Protestant Reformation spreading throughout Catholic Europe (See Martin Luther Part I page 31).

![St_Ignatius_of_Loyola_(1491-1556)_Founder_of_the_Jesuits[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/St_Ignatius_of_Loyola_1491-1556_Founder_of_the_Jesuits1.jpg) During recovery, after being seriously wounded in battle, Ignatius underwent a spiritual conversion causing him to abandon his military career and devote himself to working for God. During this time he read the “Da Vita Christi,” by Ludolph of Saxony (the result of 40 years work by the author) and this work greatly influenced Ignatius. He also experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus following which he practiced serious asceticism and prayed for seven hours a day, often in a cave. As a result, Ignatius then composed the “Spiritual Exercises,” a set of meditations, prayers and mental exercises divided into four thematic weeks during a religious retreat. In 1662 he was canonized and declared patron of all spiritual retreats and is a foremost patron saint of soldiers.

During recovery, after being seriously wounded in battle, Ignatius underwent a spiritual conversion causing him to abandon his military career and devote himself to working for God. During this time he read the “Da Vita Christi,” by Ludolph of Saxony (the result of 40 years work by the author) and this work greatly influenced Ignatius. He also experienced a vision of the Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus following which he practiced serious asceticism and prayed for seven hours a day, often in a cave. As a result, Ignatius then composed the “Spiritual Exercises,” a set of meditations, prayers and mental exercises divided into four thematic weeks during a religious retreat. In 1662 he was canonized and declared patron of all spiritual retreats and is a foremost patron saint of soldiers.

The portrait of Saint Ignatius of Loyola was painted by Peter Paul Rubens (1577 – 1640).

(109)

James next tells us that Saint John of the Cross, whom the author refers to as one of the best of the mystical teachers, describes the condition as the “union of love,” which he says, is reached by “dark contemplation” [from St. John’s book “The Dark Night of the Soul”] “… the soul then feels as if placed in a vast and profound solitude … there, in the abyss of wisdom, the soul grows by what it drinks in from the well-springs of the comprehension of love … and realizes how insignificant and improper the terms we employ are when we seek to discourse of divine things.”

In the condition called raptus, or ravishment, by theologians, breathing and blood circulation are so depressed that it is a question amongst physicians whether the soul be or not be temporarily separated from the body. James states that one must read Saint Teresa’s descriptions and the very exact distinctions which she makes claiming that one is dealing, not with imaginary experiences, but with the phenomena which, however rare, follow perfectly definite psychological types.

Yet, James continues, to the medical mind these ecstasies signify nothing but suggestive hypnotic states, based intellectually on superstition and a corporeal state of degeneration. Undoubtedly, these pathological conditions have existed in many of the cases but, that tells us nothing about the value of the knowledge imparted by these states to the consciousness. So, in order to pass a spiritual judgment here, we must not content ourselves with superficial medical talk, but inquire further as to their fruits, which have been varied. Here James reminds us of the helplessness in the kitchen and schoolroom of poor Margaret Mary Alacoque. She, like many other ecstatics, would have perished but for the care given them by admiring followers. These “other worldly” states encouraged by the mystical practice makes one whom the character is naturally passive and the intellect feeble peculiarly liable. But, insists James, in natively strong minds and characters we find quite opposite results. And here James tells us that Saint Ignatius, for example, was a mystic, but his mysticism made him assuredly one of the most powerfully practical human engines that ever lived.

(110)

L.T. – Here I am going to change direction entirely; sparked by the comments above about suggestive hypnotic states for, I think it is an important subject. James has made several references to hypnotic states; at least seven in this document so far and more in the original, full text.

On pages 94 and 95 (above) I mentioned of a “certain and specific incident of hypnosis.” I was referring to a particular realtor whom, I am convinced, was told by an attorney to contact me. This realtor was, perhaps still is, a dangerous man and I made that clear in what I wrote on those two pages. I want to describe the events associated with the hypnosis for it is possible that many crimes, and the worst types of crimes, may be committed against or by hypnotized subjects. I will tell you here exactly what happened and you can decide for yourself as to whether or not what I report here is true.

I don’t recall the exact time of day or month but it was daylight and warm outside. The main floor of the condominium (living room and art studio) and kitchen were located on the top, the rooftop actually, of the three story building; the bedroom and bathroom were on the floor below. Because of the chemicals I used, oil paints, turpentine, etc., and the comfortable weather, I would generally leave the double French doors leading to the east facing deck wide open for ventilation, plus it made for a pleasant working environment. There were no screens on the doors; insects weren’t generally a problem at that elevation and downtown.

The realtor stopped by, specifically for what reason I do not recall. We were standing facing each other at the end of the kitchen counter when he pointed to his eyes with the first and second finger of his hand and said, “look at my eyes,” which I did. He told me to keep looking at them, which I did. I thought he wanted me to focus on his eyes while he spoke, for they were his most attractive feature; other than his eyes, he was not attractive. I recall very clearly thinking that they were rather interesting looking – they seemed to protrude slightly as if on a different plane than his face. He then began to talk of a place he and his family vacationed every summer for years. It was at a cabin on a lake and that there was a dock on the property’s waterfront. He then stated that once, when he was outdoors walking, a swarm of wasps inexplicably started chasing after him. He said he couldn’t shoo or get away from them so he ran to the dock, jumped off it and into the water.

He left the studio after that, at which time, very soon thereafter in fact, a large pure black, nearly two inches long wasp flew into the studio through the open French doors and came directly after me still standing in the kitchen area. I attempted to shoo it out yet, it aggressively continued coming after me. I rolled up a newspaper and began swatting at it. Then, at one point, at the other end of the studio and facing west, away from the French doors, when I took a swat at it, it just disappeared. It was the strangest thing – I did not sense any contact between the insect and the newspaper nor did I see it fly off. The scene then repeated itself; another large black wasp flew through the open doors and came directly after me. I again swatted at it with the rolled up newspaper and the exact same thing happened; it just disappeared. I did not know what to think. I looked all over for it: behind stacked canvases, the couch, the file cabinet. There was no sight of it anywhere and, like the first one, I did not see it fly off and back outdoors.

(111)

I sat down on the couch feeling a little stunned by what had happened (not at all thinking about the story that the realtor had told me). When suddenly I saw, just outside the French doors at a hanging pot of petunias, a huge, the size of a small bird, wasp – but more like a bee. It had the characteristic gold and black striped abdomen and a fuller, less scrawny type structure typical of wasps. My immediate thought was how I wish I had a jar for I had never before seen such a huge bee, nor wasp. It very soon flew away. Then I knew exactly what had happened – the realtor had hypnotized me. And, perhaps hoping I would jump off the deck thinking I was at a lake. The hallucinations then ceased.

I want to say this because I think it is important. Sirhan Sirhan, the person who shot presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, just two months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, has claimed that prior to shooting Kennedy he had met a woman in a bar, that she had most intriguing eyes and, when he shot Robert Kennedy, he thought he was aiming at a target on a shooting range. He claims that he believes he was hypnotized by the woman. Now I think he may be telling the truth.

I am here adding something to the account posted on page (95) above about a hike I went on with the realtor. The weather during the hike along a trail in the gold mining territory was pleasant; sometimes overcast and sometimes sunny and a perfectly comfortable temperature; nothing suggestive of worse weather to come. I wasn’t in a particularly bad mood while hiking although I knew I was surrounded, back home by some dangerous people and I did believe, and do believe to this day, that the man I was with was a killer, a “hit man” to be specific. I thought he would kill, or not, on a whim almost. I did believe he wanted to keep me as a romantic companion but, I also knew he was not a rational person. I grew, to a certain degree, used to my circumstances although I wouldn’t say that I am completely over them to this day either.

As we were hiking along he ventured off the trail a bit and asked me to come to where he was: standing next to a vertical, approximately seven or eight feet high, thin (just enough width for a person to slip through) wooden framed opening to an old mine shaft. He gestured for me to look inside the shaft at which time, quite suddenly and unexpectedly, the sky turned dark, lightning and thunder struck and rain began to pour down. This caused us to immediately abandon the mine shaft and run towards the path thinking we should head for the car and leave the area all together. However, very soon after that, the sky cleared and the sun came out so we resumed our hike with the intention of staying in the wilderness. Then later, how long I do not remember but, near the end of the hike he again, venturing just off the trail, wanted to show me another opening to a mine shaft. This one was similar in size and appearance to the first one only horizontally positioned along the ground. And again, as I came up towards the opening, the sky suddenly darkened and a storm broke out causing us to run to the car. And, just like before, the storm cleared up as suddenly as it appeared. The realtor mentioned the strangeness of the two circumstances (internally, I had noted them too). I have also wondered from that day to the present what lies at the bottom of those mine shafts (skeletons perhaps?). This concern was so present in my mind for some time afterward to the extent that I felt I had to report it.

Back to the topic of mysticism:

James goes on to state that mystical conditions may, therefore, render the soul more energetic in line with which their inspiration favors. But, this could be considered an advantage only in cases where the inspirations were true ones. And, this gets us back once more to the problem of truth which confronted us at the end of the chapters on saintliness.

(112)

Here James again mentions Saint John of the Cross writing of the intuitions and “touches” by which God reaches the substance of the soul:

“They enrich it marvelously. A single one of them may be sufficient to abolish at a stroke certain imperfections of which the soul during its whole life had vainly tried to rid itself, and to leave it adorned with virtues and loaded with supernatural gifts. A single one of these intoxicating consolations may reward it for all the labors undergone in its life – even when they are numberless.”

Saint Teresa, James informs us, is as emphatic yet much more detailed [much abridged]:

“Often, infirm and wrought upon with dreadful pains before the ecstasy, the soul emerges from it full of health and admirably disposed for action … as if God had willed that the body itself, already obedient to the soul’s desires, should share in the soul’s happiness. The soul, after such a favor, is animated with a degree of courage so great that, if at that moment its body should be torn to pieces for the cause of God, it would feel nothing but the liveliest comfort. It is then that promises and heroic resolutions spring up in profusion … and our clear perception of our proper nothingness. What empire is comparable to that of a soul who, from this sublime summit to which God has raised her, sees all the things on Earth beneath her feet, and is captivated by not one of them. How amazed at her own blindness! What lively pity she feels for those whom she recognizes as still shrouded in the darkness! She groans at having ever been sensitive to what the world recognizes as honorable and calls by that name. She now sees in this name nothing more than an immense lie of which the world remains a victim. She discovers, in the new light from above, that in genuine honor there is nothing spurious, that to be faithful to this honor is to give our respect to what deserves to be respected truly, and to consider as nothing, or as less than nothing, whatsoever perishes …”

James then poses the question, do mystical states establish the truth of those theological affections in which the saintly life has its roots? He then states that it is possible to give the outcome of the majority of them in terms that point in definite philosophical directions. One of these directions is optimism and the other is monism [the view that there is only one kind of ultimate substance; that reality is one unitary wholeness]. We pass into mystical states from out of ordinary consciousness: from a less into a more, from a smallness into a vastness and, at the same time, from an unrest to peace. We feel them as reconciling, unifying states. In them the unlimited absorbs the limits and peacefully closes the account.

(113)

The author continues, whosoever calls the Absolute anything in particular, or says that it is this seems implicitly to shut of off from being that – it is as if he lessened it. So we deny the this (separate from the that), negating the negation in the interest of the higher affirmative attitude [I am that I AM].The fountain-head of Christian mysticism is Dionysius the Areopagite [around 1st century A.D.] who describes the absolute truth by the negative exclusively:

“The cause of all things is neither soul nor intellect, nor is it reason nor intelligence, nor is it spoken nor thought. It is neither number, nor order, nor magnitude, nor littleness, nor equality, nor inequality, nor similarity, nor dissimilarity, and so on.” But, James adds, these qualifications are denied by Dionysius, not because the truth falls short of them, but because it so infinitely excels them. And, to this dialectical use of negation as a mode of passage towards a higher kind of affirmation, there is correlated another form of negation; a denial of the finite self and its wants. And here is where a form of asceticism of some sort is found in religious experience to be the only doorway to the larger and more blessed life.

Here James quotes Jakob Behmen (1575 – 1624) a German mystic and theosophist (see theosophist Rudolf Steiner’s abridged book chapter (E) “How to know Higher Worlds” on this website) who founded modern theosophy and influenced George Fox (founder of the Quaker religion):

“Love is Nothing [No Thing] for, when thou hath gone forth wholly from the creature and from that which is visible, and become Nothing to all that is Nature and Creature, then thou art in that eternal One, which is God Himself, and then thou shall feel within thee the highest virtue of Love – the treasure of treasures. For, the soul is out of the somewhat into that Nothing out of which all things may be made. The soul here saith, I have nothing, for I am utterly stripped and naked; I can do nothing for I have no manner of power; I am as water poured out; I am nothing for that ‘I am’ is no more; and only God is to me. I AM.”

James continues, this overcoming of all the usual barriers between the individual and the Absolute is the great mystic achievement. In mystic states we both become one with the Absolute and aware of our oneness. This is the everlasting and triumphant of the mystical tradition, hardly altered by differences of faith or ideology. In Hinduism, in Neoplatonism, in Sufism, in mysticism, in Whitmanism [as in Walt Whitman and healthy-mindedness], we find the same recurring note in mystical utterances: an eternal unanimity which ought to make a critic stop and think.

(114)

Here James quotes from numerous texts: “Thou art Thou” say the Upanishads. And to that the Vedantists add, “Not a part, not a mode of That, but identically That; that Absolute Spirit of the World.” “As pure water poured into pure water remains the same, thus, O Gautama, [the Buddha] is the Self of a thinker who knows. Water in water, fire in fire, ether in ether, no one can distinguish them; likewise a man whose mind has entered into the Self.” “Every man,” says the Sufi Gulshan-Raz, “whose heart is no longer shaken by any doubt, knows with certainty that there is no being save the only One … In his divine majesty the me, and we, the thou, are not found, for in the One there can be no distinction. Every being who is annulled and entirely separated from himself, hears resounding in this voice and this echo: I am God.” In the vision of God, says Plotinus, “What sees is not our reason but something other and superior to our reason.”