INTRODUCTION

This is an abridged version (or in-depth review) of William James’ classic “The Varieties of Religious Experience.” Along with the content from James’ book, included are numerous brief biographies of individuals featured in his book (for example, Tolstoy, Voltaire, Cromwell, Tennyson, Hegel, Martin Luther). A reader of this work should find it of historical, social, as well as religious, or spiritual, significance. It is also, at times, a humorous piece therefore, it is not only intellectually enlightening but an exceedingly enjoyable read. James is an extraordinary intellect and communicator and thus it is a humble task to dare to contract, and sometimes rework (although infrequently) in contemporary parlance his ingenious work.

I must also add, for this is important, that this work, “The Varieties of Religious Experience” is not at all intended as a promulgation of the Christian faith. Let us remember that it was produced over a hundred years ago and William James is an American and, the book is based on lectures, the Gifford Lectures, given by him at the University in Edinburgh, Scotland. Christianity is the common faith of that time and geography. I should also state that, whereas a writer today might use the word ‘spiritual’ in place of the word ‘religious’ (as James so often uses) here again we should not let our contemporary and personal views interfere with the meaningfulness and importance of the author’s treatise.

Another important qualification that I must make has to do with the numerous quotations in the work. James relies on a number of sources; excerpts from various books, letters, and other documents, to illustrate his points. While I find it necessary to, at times, alter the wordage from these sources (ever so slightly and always true to the statements made) for the sake of clarity, brevity and flow I maintain the use of the quotation marks to denote the many sources of testimony other than those statements made by William James. I regret tainting the intended genuineness of a quoted statement but, in this particular case, I can see no other, better way.

This is an intellectual piece; not quick and easy information. It’s worth the investment of time and effort to learn of the many fascinating accounts of religious and mystical experiences of [for the most part western culture] renown individuals and their subsequent influence on humankind’s, including the reader’s, spiritual evolution. James’s book is probably the best (and truly fascinating) source for this study.

* Also, in general, the italicized text indicates my comments [prefaced by an L.T.]. Although, on occasion, James italicized words which I kept as they are in his book.

Leslie Taylor – October 2015

![3a317[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/3a3171-200x300.jpg) William James (1842 – 1910) was a psychologist and American philosopher and also trained as a physician. He was the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States. James is believed by many to be one of the leading thinkers of the late nineteenth century and one of the most influential philosophers in the United States. Others consider him the father of American psychology.

William James (1842 – 1910) was a psychologist and American philosopher and also trained as a physician. He was the first educator to offer a psychology course in the United States. James is believed by many to be one of the leading thinkers of the late nineteenth century and one of the most influential philosophers in the United States. Others consider him the father of American psychology.

He was born into a wealthy family in the Astor House in New York City; the son of a prominent and independently wealthy Swedenborgian theologian Henry James Sr. (see Emanuel Swedenborg at the end of Lecture l) who was well acquainted with the literary and intellectual elites of his day. William James was the brother of the prominent novelist Henry James (i.e.,“The American,” “Portrait of a Lady,” “The Wings of the Dove”) and the diarist Alice James (her diary, which she kept towards the end of her life, was published posthumously). James wrote on many topics including epistemology, education, metaphysics, psychology, religion and mysticism. His most renown and influential books are: “The Principles of Psychology,” “Essays in Radical Empiricism,” and “The Varieties of Religious Experience” which is an investigation into the different forms of the religious experience, and the subject of this review.

Source: Wikipedia

THE VARIETIES OF RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part I

- Preface – Page 1

- Lecture I – Religion and Neurology – pages 1 – 5

- Lecture II – Circumscription of the Topic – pages 6 – 10

- Lecture III – The Reality of the Unseen – pages 11 – 14

- Lectures IV and V – The Religion of Healthy-Mindedness – pages 15 – 21

- Lectures VI and VII – The Sick Soul – pages 22 – 23

- Lectures VIII – The Divided Self and the Process of Its Unification – pages 23 – 36

- Lecture IX – Conversion – pages 36 – 42

- Lecture X – Conversion (continued) – pages 43 – 53

Part II

- Lectures XI, XII, and XIII – Saintliness – pages 54 – 76

- Lectures XIV and XV – The Value of Saintliness – pages 77 – 90

Part III

- Lectures XIV and XV – The Value of Saintliness (continued) – pages 91 – 98

- Lectures XVI and XVII – Mysticism – pages 99 – 117

- Lecture XVIII – Philosophy – pages 118 – 136

- Lecture XX – Conclusions – pages 137 – 148

- Postscript – pages 149 – 151

PREFACE

The “Varieties of Religious Experience” is the series of lectures given by William James who had been honored as Gifford Lecturer at the University of Edinburgh, 1901 – 1902. The description of man’s religious constitution is the subject of the twenty lectures.

The author chooses to acquaint his readers with specific examples of the religious personality rather than an abstract, philosophical, however deep, analysis believing this will make us wiser on the topic. And, has chosen the known, or concrete, incidents amongst reports of the more extreme examples of the religious temperament, or personality. The reader may eventually regard the book as “to supply a caricature of the subject.” James states, “Such convulsions of piety, they will say, are not sane. If, however, they will have the patience to read to the end, I believe that this unfavorable impression will disappear …”

Lecture I – RELIGION AND NEUROLOGY

The author begins by stating, “I am neither a theologian, nor a scholar learned in the history of religions, nor an anthropologist. Psychology is the only branch of learning in which I am particularly versed. To the psychologist, the religious propensities of man must be at least as interesting as any other of the facts pertaining to his mental constitution. And, if the inquiry be psychological, not religious institutions, religious feelings and impulses must then be its subject.”

Therefore James confines himself to those developed subjective phenomena recorded in literature produced by articulate and fully self-conscious men, in works of piety and autobiography. It then follows from this, the documents that will most concern us will be those of the men who were most accomplished in the religious life and best able to give an intelligible account of their ideas and motives. These men are either relatively modern writers or else such earlier ones as to have their works become religious classics.

What are the religious propensities and, what is their philosophical significance? In books on logic, distinctions are made between two orders of inquiry concerning anything. First, what is its nature (its existential – in other words, its empirical, observational, qualities) and how did it come about (its origin and history)? And secondly, what is its importance, its meaning or significance now that it is here? If judged existentially (it’s observational qualities) only, we might then induce a spiritual judgment on the Bible’s worth. For, it must contain no scientific or historical errors and express no regional or personal passions. Thus then, the Bible would fare ill at our hands. On the other hand, a book may very well be a revelation in spite of errors and passions and deliberate human composition; that is, if it be a true record of the inner experiences of great-souled persons wrestling with the crises of their fate, the verdict would then be much more favorable. Thus, you can see here that the existential, observational facts by themselves are insufficient for determining value.

There can no doubt that a religious life, exclusively pursued, does tend to make the person exceptional and eccentric whether he be Buddhist, Christian or Mohammedan. For the ordinary follower, their religion has been made for them by others; communicated by tradition, determined to fixed forms by imitation, and retained by habit. It profits us little to study this secondhand religious life. We therefore search for the original experiences which are the pattern-setters to all this mass of religious feeling and imitated conduct. These extraordinary experiences we can only find in individuals for whom religion exists not as a dull habit but rather, as an acute fever. Religious geniuses, like geniuses of any field, have tended to show symptoms of nervous instability, James contends. And, more perhaps than other kinds of genius, religious leaders have been subject to abnormal psychical visitations. They, quite possibly, have been liable to obsession and fixed ideas; and frequently they have fallen into trances, heard voices, seen visions and presented all sorts of peculiarities which are, to the ordinary and thus are ordinarily, classified as pathological.

(1)

![George_Fox[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/George_Fox1.jpg) Here James provides a concrete example: George Fox (1624 – 1691) the founder of the Quaker religion (see top of page 5 below Annie Bessant’s picture for a brief description). While the Quaker religion is something which cannot be overpraised (I encourage the reader to learn of the Quaker religion if not familiar), Fox was anything but unsound according to everyone who confronted him personally. For, the likes of Oliver Cromwell to city magistrates, to the jailer, etc., seems to have acknowledged his superior power. Yet, from the point of view of his nervous constitution, Fox was a psychopath of the deepest dye. His journal abounds with entries of this sort:

Here James provides a concrete example: George Fox (1624 – 1691) the founder of the Quaker religion (see top of page 5 below Annie Bessant’s picture for a brief description). While the Quaker religion is something which cannot be overpraised (I encourage the reader to learn of the Quaker religion if not familiar), Fox was anything but unsound according to everyone who confronted him personally. For, the likes of Oliver Cromwell to city magistrates, to the jailer, etc., seems to have acknowledged his superior power. Yet, from the point of view of his nervous constitution, Fox was a psychopath of the deepest dye. His journal abounds with entries of this sort:

“As I was walking with several friends, I lifted up my head, and saw three steeple-house spires, and they struck at my life. I asked them what place that was? They said, Lichfield. Immediately the word of the Lord came to me, that I must go thither. Being close to the house we were going to, I wished the friends to walk into the house, saying nothing to them of whither I was to go. As soon as they were gone I stepped away, and went by my eye over hedge and ditch till I came within a mile of Lichfield; where, in a great field, shepherds were keeping their sheep. Then was I commanded by the Lord to pull off my shoes. I stood still, for it was winter: but the word of the Lord was like a fire in me. So I took off my shoes and left them with the shepherds; and the poor shepherds trembled and were astonished. Then I walked on about a mile, and as soon as I was within the city, the word of the Lord came to me again, saying: Cry, “Wo to the bloody city of Lichfield!” So I went up and down the streets, crying with a loud voice, “Wo to the bloody city of Lichfield!” It being market day, I went into the market place and to and fro in the several parts of it, and made stands, crying as before, “Wo to the bloody city of Lichfield!” And no one laid hands on me.”

“As I went thus crying through the streets, there seemed to me to be a channel of blood running down the streets and the market place appeared like a pool of blood. When I declared what was upon me, and felt myself clear, I went out of the town in peace; and returning to the shepherds gave them some money, and took my shoes off them again. But, the fire of the Lord was so on my feet and all over me, that I did not matter to put my shoes on again, and was at a stand whether I should or not, till I felt freedom from the Lord to do so: then, after I had washed my feet, I put on my shoes again. After this a deep consideration came upon me, for what reason should I be sent to cry against the city, and call it “the bloody city!”? For [in the past] the parliament had the one minister while, and the king another and much blood had been shed during the wars between them. Yet, there was no more than had befallen many other places. But afterwards I came to understand that in the Emperor Diocletian’s time a thousand Christians were martyred in Lichfield. So I was to go, without my shoes, through the channel of their blood, and into the pool of their blood in the marketplace, that I might raise up the memorial of the blood of those martyrs, which had been shed above a thousand years before, and lay cold in their streets. So, the sense of this blood was upon me, and I obeyed the word of the Lord.”

(2)

James then professes, that upon studying religion’s existential condition, we simply cannot possibly ignore these pathological aspects of the subject. Yet, he goes on to quote Spinoza, “I will analyze the actions and appetites of men as if it were a question of lines, of planes, and of solids.” And similarly, the “Spectator” critic, M. Taine writes, “Whether facts be moral or physical, it makes no matter – they always have their causes. There are causes for ambition, courage, and veracity, just as there are for digestion, muscular movement, and animal heat. Vice and virtue are products like vitriol [a sulfate – or salt] and sugar.” James indignantly remarks that when we read of such cold blooded assimilations, bent on showing the existential condition of absolutely everything; explaining our soul’s being and influence thus making them appear no more precious than groceries, we feel menaced and negated in the very springs of our innermost life.

James cites examples of medical materialism by unsentimental people on their more sentimental acquaintances; undoing their spiritual value. For example: Alfred believes in immortality so strongly because his temperament is so emotional. William’s melancholy about the universe is due to bad digestion – probably his liver is torpid. Eliza’s delight in her church is a symptom of her hysterical condition, and so on. The author here adds, there is not a single one of our states of mind, high or low, healthy or ill, that has not some organic process as its condition. Scientific theories are organically conditioned just as much as religious emotions are; and, if we could only know the facts intimately enough, we should no doubt see “the liver” determining the dicta of the sturdy atheist as decisively as it does those of the Methodist anxious about his soul.

Such physicalist claims, as those asserted above, are quite illogical and arbitrary unless one has worked out in advance some psycho-physical theory connecting spiritual values in general with physiological change. Otherwise none of our thoughts and feelings, not even our scientific doctrines, not even our disbeliefs, could retain any value as revelations of the truth. For, every one of them, without exception, does indeed flow from the state of its possessor’s body at any given time. If there is no physiological theory with which to accredit the favored states, then conversely, any attempt to discredit the states which are disliked (by associating them with nerves and the liver by giving them names connoting them with bodily afflictions) is altogether illogical and inconsistent. In the natural sciences and industrial arts it never occurs to anyone to try to refute opinions by showing up their author’s neurotic constitution. Opinions here are invariably tested by logic and experiment, no matter what may be their author’s neurological type. It should not be otherwise with religious opinions.

James adds, then, of course, there is the medical materialist’s criticizing of the religious life connecting it with the sexual life. Conversion [religious] is a crisis of adolescence, and for the hysterical nun Christ is but an imaginary substitute for a more earthly object of affection.

On genius, James here tells us that others, such as: Dr. Moreau states, “… is but one of the many branches of the neuropathic tree.” “Genius, says Dr. Lombroso, “is but a symptom of hereditary degeneration …” and Mr. Nisbet, writes “… the greater the genius, the greater the unsoundness.” James asks, do these authors, now having satisfied themselves that the works of geniuses are the fruits of diseased minds and they thereupon proceed to impugn the value of the fruits? No! he exclaims. For their spiritual instincts are too strong here and hold their own against such inferences if, for no other reason, but for logical consistency.

(3)

Dr. Maudsley , according to James, is perhaps the cleverest of the rebutters of supernatural religion on grounds of origin. Yet, he writes:

“What right have we to believe Nature is under any obligation to do her work by means of complete minds only? She may find an incomplete mind a more suitable instrument for a particular purpose. It is the work that is done, and the quality in the worker by which it was done which may be of no great matter from a cosmic standpoint should other qualities of character he possessed were singularly defective – if he indeed were a hypocrite, adulterer, eccentric, or lunatic.”

In other words, not its origin, but the way in which it works on the whole, is Dr. Maudsley’s final test of a belief. It is this empiricist criterion that even the stoutest insisters on supernatural origin have also been forced to use in the end. For, among the visions and messages some have always been too patently silly. And, among the trances and convulsive seizures some have been too fruitless in their conduct and character, to pass themselves off as significant, still less as divine. In the history of Christian mysticism the problem of how to discriminate between such messages and experiences as being really divine miracles, as possibly the demon in his malice as able to counterfeit, thus making the religious person more the child of hell, has always been a difficult one to solve needing all the sagacity and experience of the best directors of conscience. In the end it had to come to the empiricist criterion: By their fruits ye shall know them, not by their roots.

James here includes a statement by Saint Teresa on possible deception by the tempter:

“Like disturbed sleep which, instead of giving more strength to the head, doth but leave it more exhausted, thus too the results of the operations of the imagination; its effects but weaken the soul; instead of nourishment and energy one reaps only lassitude and disgust. Whereas a genuine heavenly vision yields to a harvest of ineffable spiritual riches and an admirable renewal of bodily strength. I alleged these reasons of those who so have often accused my visions of being the work of the enemy of mankind and the sport of my imagination. I showed them the jewels which the divine hand had left with me: those being my actual dispositions. All those who knew me saw that I was changed; my confessor bore witness to the fact; this improvement, palpable in all respects and far from being hidden, was brilliantly evident to all men. As for myself, it was impossible to believe that if the demon were its author, he could have used, in order to lose me and lead me to hell, an expedient so contrary to his own interests as that of uprooting my vices and fill me with masculine courage and other virtues instead. For, I saw clearly that a single one of these visions was enough to enrich me with all that wealth.”

James then writes of religious phenomena and the melancholy which often constitutes an essential moment in every complete religious evolution. As well, he mentions cranky temperaments and that they tend to possess extraordinary emotional susceptibility such as fixed ideas and obsessions . And, that such an individual’s conceptions tend to pass immediately into belief and action; that when they get a new idea, they have no rest until it somehow “works itself off.” He refers to a passage in the autobiography of whom he refers to as “that high-souled” woman,” Annie Besant:

Plenty of people wish well to any good cause, but very few care to exert themselves to help it, and still fewer will risk anything it supports. “Someone ought to do it, but why should I?” is the ever re-echoed phrase of the weak-kneed amiable personality. Whereas, “Someone ought to do it, so why not I?” is the cry of the earnest servant of man, eagerly forward springing to face some perilous duty. Between these two sentences lie whole centuries of moral evolution.

“True enough!” proclaims James.

(4)

Quakers or Religious Society of Friends (est. in England in the mid-1600s) – is a Christian movement which professes the priesthood of all believers. It avoids authoritative creed and hierarchical structures and includes those with evangelical, liberal and conservative understandings of Christianity. The founder, George Fox, being dissatisfied with the teachings of the Church of England, had a revelation and thus became convinced that it was possible for anyone to have a direct experience of Christ without the aid of an ordained clergy. Presently, less than half of ‘Friends’ practice programmed worship with a prepared message from the Bible coordinated by a pastor. But rather, worship is predominantly silent and may include unprepared vocal ministry from those present.

In North America in the 1600’s, and while some Quakers experienced persecution, they established thriving communities in West Jersey, Rhode Island and Pennsylvania (with the West Jersey and Pennsylvania colonies having been established by the affluent Quaker, William Penn). In 2007 there were approximately 370,000 adult Quakers.

Emanuel Swedenborg (1688 – 1772) Recall that William James’s father, Henry James Sr., was a Swedenborgian. Swedenborg had a successful career as an inventor and scientist. In 1741, at 53 years old, he entered the spiritual phase of his life where he began to experience dreams and visions. For the remaining 28 years of his life, Swedenborg wrote eighteen published theological works and several more which were not published. In his self-published work “True Christian Religion” he refers to himself as a “Servant of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

He had studied anatomy and physiology and had the first concept of the neuron that, not until a century later, did science recognize the nerve cell. He also had prescient ideas about the cerebral cortex, the hierarchical organization of the nervous system, the localization of the cerebrospinal fluid, functions of the pituitary gland and other neurological systems. However, it was his published works conjoining philosophy and metallurgy that gave him international recognition (in particular, his analysis of the smelting of iron and copper).

![220px-Emanuel_Swedenborg[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/220px-Emanuel_Swedenborg1.png) Swedenborg experienced well documented prophetic and psychic abilities. For example, he became quite agitated when a great fire broke out in Stockholm, Sweden in 1759. At the time he was at a dinner party 400 kilometers from his home in Stockholm. He told those present about the fire and that it had consumed a neighbor’s home and was threatening his own. Two hours later he exclaimed with relief that the fire had stopped three doors from his home. News of his psychic perception of the fire spread quickly reaching the provincial governor who summoned him for details (given that news from Sweden to Gothenburg otherwise took three days to arrive by messenger). On another occasion, Queen Louisa Ulrika of Sweden asked him to tell her something about her deceased brother. What he whispered to her caused her to turn pale and she explained that it was something only she and her brother could possibly know about. Swedenborg also predicted the date of his own death, March 29, and a servant girl reported that he was as happy about it as if he was “going on holiday or to some merry making.”

Swedenborg experienced well documented prophetic and psychic abilities. For example, he became quite agitated when a great fire broke out in Stockholm, Sweden in 1759. At the time he was at a dinner party 400 kilometers from his home in Stockholm. He told those present about the fire and that it had consumed a neighbor’s home and was threatening his own. Two hours later he exclaimed with relief that the fire had stopped three doors from his home. News of his psychic perception of the fire spread quickly reaching the provincial governor who summoned him for details (given that news from Sweden to Gothenburg otherwise took three days to arrive by messenger). On another occasion, Queen Louisa Ulrika of Sweden asked him to tell her something about her deceased brother. What he whispered to her caused her to turn pale and she explained that it was something only she and her brother could possibly know about. Swedenborg also predicted the date of his own death, March 29, and a servant girl reported that he was as happy about it as if he was “going on holiday or to some merry making.”

Here [below] is a link to an excellent website about Swedenborg’s life and teachings from the Swedenborg Foundation. They provide on their site free PDF files for download of Swedenborg’s many books and numerous informative, and most entertaining, videos of Swedenborg’s teachings.

And here, as example, is one of the Swedenborg Foundation’s many videos. It is very well done, fun and educational.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M85ttx9Hzm0

(5)

Lecture II – Circumscription of the Topic

Religion – James advises us not to fall into a one sided view of the subject of religion but to admit at the outset that we shall very likely find, not one essence, but rather many characteristics that may be alternately equally important to religion. He goes on to state, that in the philosophies and psychologies of religion we find those attempting to specify just what religion is: with one allying it to the feeling of dependence, another making it a derivative of fear, others connecting it with the sexual life with still others identifying it with the feeling of the infinite, and so on, thus giving the subject a certain multiplicity arousing doubt that it can be any one thing. Adding to this, there is religious fear, religious love, religious awe, religious joy and so forth. But, religious love, claims the author, is only man’s natural emotion of love. Religious fear is, similarly, the ordinary fear of commerce [this for that] based in so far as the notion of divine retribution may arouse fear. And religious awe is the same thrill which we feel in a forest at twilight, or at a mountain gorge, only here it comes over us at the thought of the supernatural, rather than the experience of the natural environment.

Therefore, James surmises, as there seems to be no one elementary religious emotion but rather a common storehouse of emotions from which religious objective may draw, thus conceivably proving that there be no one specific and essential kind of religious objective and no one specific and essential kind of religious expression.

One is also struck at the great partition which divides the religious field. On the one side we have the institutional and, on the other, personal religion. Worship and sacrifice, procedures for working on the understanding and disposition of the deity, ceremony and ecclesiastical organization are the essentials of religion in the institutional branch. Should we limit our view to it, we should define institutional religion as an external art – the art of winning the favor of the gods. The more personal branch is, on the contrary, the inner disposition of man himself which forms his religious perspective: his conscience, his deserts, his helplessness, his incompleteness. Although, like in the institutional, the favor of the God (as either forfeited or gained) is still an essential feature. James states that he proposes to here ignore the institutional branch entirely and confine his thesis to personal religion, pure and simple, as much as is possible.

He also addresses fetishism and magic and states that they seem to have preceded inward piety historically – or, at least, records of inward piety do not reach back so far. He says that many anthropologists claim that the whole system of belief leading to magic, fetishism and the lower superstitions may be considered as primitive religions.

On personal religion, he asks the reader to take it to mean it is the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the Divine. He also adds that there are systems of thought which the world usually considers religious but which do not positively assume a God. Buddhism, for example, is such a case. Popularly, the Buddha himself stands in place of a god but, in strictness the Buddhistic system is atheistic. Modern Transcendental Idealism, Emersonianism for instance, seems to let God evaporate into an abstract ideality; not a deity in a concrete sense; in other words, not a superhuman person. But rather the immanent divinity in all things; the spiritual structure of the universe. The paragraph below is derived from a lecture given by Ralph Waldo Emerson (biography below) at Divinity College in 1838. According to James it was this lecture that made Emerson famous.

(6)

Emerson’s lecture:

“These laws, said the speaker, execute themselves. They are out of time, out of space, and not subject to circumstance: Thus, in the soul of man there is a justice whose retributions are instant and entire. He who does a good deed is instantly ennobled. He who does a mean deed is, by the action itself, contracted. He who puts off impurity thereby puts on purity. If a man is at heart just, then in so far, is he God; the safety of God, the immortality of God, the majesty of God, do enter into that man with justice. If a man deceives, he deceives himself and goes out of acquaintance with his own being. Character is always known. Thefts never enrich; alms never impoverish; murder will speak from out of stone walls. The least admixture of a lie (for example: for vanity, to make a good impression or a favorable effect) will instantly vitiate, or spoil, the effect. But speak the truth and all things alive are validation; the very roots of the grass underground there do seem to stir and move to bear your witness. For, all things proceed out of the same Spirit, which is differently named love, justice, temperance, and Its different applications, just as the ocean receives different names on the several shores which it washes. In so far as he roves from these ends, a man bereaves himself of power, of auxiliaries. His being shrinks … he becomes less and less: a mote, a point, until absolute badness is absolute death.”

“The perception of this law awakens in the mind a sentiment which we call the religious sentiment, and which makes our highest happiness. Wonderful is its power to charm and to command; it is a mountain air; it is the balm of the world. It makes the sky and the hills sublime and is the silent song of the stars. It is the beatitude of man. It makes him without limit or end. When he says ‘I ought’; when love warns him; when he chooses thus warned from on high, the good and great deed. Then, deep melodies wander through his soul from supreme wisdom. He can then worship and be enlarged by this worship for, he can never be beneath this sentiment. All the expressions of these sentiments are sacred and permanent in proportion to their purity. They affect us more than all other compositions. The sentences of the olden times, which ejaculate this piety, are still fresh and fragrant. And, the unique impression of Jesus upon mankind, whose name is not so much written as it is ploughed, is infused, into the history of the world, is proof of the subtle virtue of this infusion.”

Such is the Emersonian religion, James tells us. The universe has a divine soul of order in which soul is moral, being also the soul within the soul of man. The sentences in which Emerson, to the very end, gave utterance to this faith are as fine as anything in literature:

“If you love and serve men, you cannot by any hiding or stratagem escape the remuneration. Secret retributions are always restoring the lever, when disturbed, of the divine justice. It is impossible to tilt the beam. All the tyrants and proprietors and monopolists of the world in vain set their shoulders to heave the bar.”

(7)

James continues, the term “godlike” if treated as a floating general quality, becomes exceedingly vague, for many gods have flourished in religious history and their attributes have been differing enough. Yet, for the most part, Gods are conceived to be first things in the way of being and power. They overarch and envelop and from them there is no escape. All that relates to them is the first and last word in the way of truth. Whatever then is considered most primal, enveloping and deeply true might be treated as godlike, and man’s religion might thereby be identified with his attitude; what he believes to be the primal truth. Religion, whatever it is, is a man’s total reaction upon life. And, total reactions are different from casual reactions. And total attitudes are different from causal or professional attitudes. To get at them you must go behind the foreground of existence and reach into that curious sense of the whole of the vestigial cosmos as an everlasting presence. Yet, he points out, there are those trifling, sneering attitudes even toward the whole of life. Voltaire (see image of bust and brief biography, page 10) for example, at the age of 73, writes to a friend:

“Weak as I am, I carry on the war to the last moment, I get a hundred pike-thrusts, I return two hundred, and I laugh. I see near my door, Geneva on fire with quarrels over nothing, and I laugh again. And, thank God I can look upon the world as a farce even when it becomes as tragic as it sometimes does. All comes out even at the end of the day, and all comes out still more even when all the days are over.”

Yet, James notes: “Much as we may admire such a robust old gamecock spirit, to call it a religious spirit would be odd.” Along similar lines, “All is vanity” is the relieving word in all difficult crises for the mode of thought with which that exquisite literary genius Renan took pleasure in his later days:

“There are many chances that the world may be nothing but a fairy pantomime of which no God has care. Be ready for anything – that perhaps is wisdom. Give ourselves up, according to the hour, to confidence, to skepticism, to optimism, to irony, and we may be sure that at certain moments, at least, we shall be with the truth … for, good humor is a philosophic state of mind: it seems to say to Nature that we take her no more seriously than she takes us! We owe it to the Eternal to be virtuous but, we have the right to add to this tribute our own irony as a sort of personal reprisal. In this way … jest for jest, we play the trick that has been played on us.”

And, Saint Augustines’ phrase: “Lord, if we are deceived, it is by thee!” remains a fine one.

On this James asserts that for common men, however, religion signifies a more serious state of mind and the phrase “all is not vanity in this universe” better signifies the universal message whatever appearances may otherwise suggest. But, if hostile to light irony religion is equally hostile to heavy grumbling and complaint. The world appears tragic enough in some religions but, the tragedy is realized as a purging and a way of deliverance. Regardless, there must be something solemn, serious and tender about any religious attitude. If glad, it must not grin nor snicker; if sad, it must not scream nor curse. Here James proposes that the divine shall mean for us only such a primal reality as the individual feels impelled to respond to solemnly and gravely, and neither by a curse nor a jest. But, he goes on, the boundaries are always misty and it is everywhere a question of amount and degree. Nevertheless, at their extreme development, there is no question as to what experiences are indeed religious and therefore nobody can be tempted to call it anything else. The only cases likely then to be of value to us to give our attention to, will be the cases where the religious experience is unmistakable and extreme. Its fainter manifestations we shall tranquilly pass by.

(8)

Here the author considers two differing states; not so much a difference of doctrine, but rather it is a difference of mood that parts them: First, the stoic Marcus Aurelius (121 – 180 AD) as he coldly reflects on the eternal reasoning that has ordered things and secondly, the Christian ejaculations expressed by the old Christian author of the Theologia Germanica that God is here to be loved:

“It is a man’s duty,” says Marcus Aurelius, “to comfort himself and wait for the natural dissolution, and not to be vexed but, to find refreshment solely in these thoughts – first that nothing will happen to one which is not conformable to the universe; and secondly, that I need do nothing contrary to the God and deity within me for there is no man who can compel me to transgress. And so to accept everything which happens, even if it seems disagreeable, because it leads to this: the health of the universe and the prosperity and felicity of Zeus.”

And here from Theologia Germanica: “Where men are enlightened with the true light … such men are in a state of freedom, because they have lost the fear of pain or hell; replaced with the hope of reward or Heaven. And, they are living in pure submission to the Eternal Goodness in the perfect freedom of fervent love. When a man truly perceiveth and considereth himself … and findeth himself utterly vile and wicked and unworthy, he falleth into such a deep abasement that is seemeth to him reasonable that all creatures in Heaven and Earth should rise up against him and he will not and dare nor desire any consolation and release. This Hell and this Heaven are two good safe ways for a man, and happy is he who truly findeth them.”

James notes how much more active and positive the impulse of the Christian writer to accept his place in the universe. Marcus Aurelius agrees to the scheme – the German theologian agrees with it. He literally abounds in agreement! He runs out to embrace the divine degrees!

Still on the topic of religion yet, from another point of view, James contends that the religious life is manly, stoical, moral, or philosophical as it is less swayed by paltry personal considerations and more so by objective ends that call for energy. Even though that energy should bring about personal loss and pain. This is the good side of war, in so far as it calls for “volunteers.” For high morality, life is a war. And, for morality, the service of the highest is a sort of cosmic patriotism which calls for volunteers. Even a sick man, unable to be militant outwardly, can carry on the moral warfare. The “athletic” attitude nonetheless tends ever to break down even amongst the most stalwart moralist when the organism begins to decay or when morbid fears invade the mind. To recommend personal will and effort to one all “sicklied o’er” and realizing his irremediable impotence is to suggest the most impossible of things. What he then craves is to be consoled in his very powerlessness; to feel that the spirit of the universe recognizes and secures him all decaying and failing as he is. Let’s face it, are we not all such helpless failures in the last resort? For it is then that the sanest and best of us are of one clay with lunatics and prison inmates and death finally runs even the robustest of us down.

L.T. – Here, here! Bartender, please …

But wait … It is here that religion comes to our rescue [not booze?] and takes our fate into her hands says James. There is a state of mind, known to religious men, but to no others, in which the will to assert ourselves and hold our own has been replaced by a willingness to close our mouths and be instead as nothing in the floods and waterspouts of God. And it is here that fear is not held in abeyance as it is by mere morality, but rather it is positively expunged and washed away. And this enchantment, coming as a gift when it does come, theologians say, is a gift of God’s grace.

(9)

James then informs us that those familiar with the Persian mystics know how wine may be regarded as an instrument of religion. Indeed, in all countries and in all ages, some form of physical enlargement – singing, dancing, drinking, sexual excitement – has been intimately associated with worship. Even the momentary expansion of the soul in laughter is, however slight an extent, a religious exercise. It is the infinite for which we hunger and we ride gladly on every little wave that promises to carry us towards it.

If one should ask how religion thus falls on the thorns and faces of death and, in the very act annuls annihilation, James says he cannot explain the matter. For, it is religion’s secret and, to understand it, you must yourself have been a religious man of the extremer type. However, he goes on to state that in future examples we shall find even amongst the healthiest-minded type of religious consciousness, a complex sacrificial constitution in which a higher happiness holds a lower unhappiness in check.

James then cites a painting by Guido Reni featuring St. Michael with his foot on Satan’s neck. He writes, “The richness of the painting is partly due to the fiend’s figure being there. That is to say, the world is all the richer for having a devil in it – so long as we keep our foot upon his neck!”

James suggests: For, when all is said and done, we are in the end absolutely dependent on the universe where into sacrifices and surrenders of some sort we are drawn and thus they are pressed upon us. Now, in those states of mind which fall short of religion, the sacrifice is submitted to as an imposition out of necessity and the sacrifice is undergone, at the very best, without complaint. On the contrary in the religious life: surrender and sacrifice are positively espoused; even unnecessary givings-up are further added in order that the happiness may increase. Religion thus makes easy and felicitous those sacrifices which in any case are necessary. And, if it be the only agency that can accomplish this result then its vital importance as a human faculty stands vindicated beyond dispute.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1922) was born in Boston, Massachusetts. His formal education was at Boston Latin School and later, at 14 years of age, Harvard. He was good friends with Prince Achille Murat, Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew, two years older than he, and the two frequently engaged in lively discussions on religion, society, government and philosophy. He considered Murat an important figure in his intellectual development. Emerson was an American writer, poet, and lecturer and leader of the Transcendentalist movement which espouses a non-traditional appreciation of nature suggesting that the divine, or God, suffuses, or permeates, throughout nature.

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803 – 1922) was born in Boston, Massachusetts. His formal education was at Boston Latin School and later, at 14 years of age, Harvard. He was good friends with Prince Achille Murat, Napoleon Bonaparte’s nephew, two years older than he, and the two frequently engaged in lively discussions on religion, society, government and philosophy. He considered Murat an important figure in his intellectual development. Emerson was an American writer, poet, and lecturer and leader of the Transcendentalist movement which espouses a non-traditional appreciation of nature suggesting that the divine, or God, suffuses, or permeates, throughout nature.

Francois-Marie Arouet – otherwise known as Voltaire (1694 –1778) was a French Enlightenment writer, historian and philosopher famous for his wit, his attacks on the Catholic Church and his advocacy of freedom of religion, freedom of expression and the separation of church and state. He was a versatile and prolific writer producing works including plays, poems, novels, essays, historical and scientific works. He wrote more than 2,000 books and pamphlets. As a political satirist, he made use of his works to criticize intolerance, religious dogma and the French institutions of his day.

![220px-Voltaire_by_Jean-Antoine_Houdon_(1778)[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/220px-Voltaire_by_Jean-Antoine_Houdon_17781-167x300.jpg) His father was a lawyer and his mother was from a noble family. Voltaire was one of five children of which three survived. In school he learned Latin and Greek and later became fluent in Italian, Spanish and English. His wit made him quite popular amongst the aristocratic families with whom he mixed. He became quite wealthy due partly to an inheritance and partly due to his own efforts.

His father was a lawyer and his mother was from a noble family. Voltaire was one of five children of which three survived. In school he learned Latin and Greek and later became fluent in Italian, Spanish and English. His wit made him quite popular amongst the aristocratic families with whom he mixed. He became quite wealthy due partly to an inheritance and partly due to his own efforts.

Voltaire was imprisoned in Bastille without a trial nor an opportunity to defend himself the result of a dispute he had with a young French nobleman. Fearing an indefinite imprisonment, Voltaire convinced the authorities that he be exiled to England as an alternative punishment. It was following his release from prison that he changed his name to Voltaire partly intending to separate himself from his past and his family. A month before his death he was initiated into Freemasonry on the recommendation of his close friend, Benjamin Franklin. But, it is supposed he did this to please Franklin.

There is so much more that can be said about this fascinating person. I recommend the reader do further research on Voltaire.

(10)

Lecture III – THE REALITY OF THE UNSEEN

Should one be asked, James posits, to characterize the life of religion in the most general terms possible, one might say that it consists of the belief that there is an unseen order, and that our supreme good lies in harmoniously adjusting ourselves thereto. All of our attitudes, moral, practical, emotional, as well as religious, are due to the “objects” of our consciousness, whether in actuality or ideally, along with ourselves. He goes on to say, such objects may be present to our senses, or they may be present only as our thoughts. In either case, they elicit from us a reaction; and, reactions due to things of thought (notoriously in many cases) are as strong as those concretely presented to our senses. For example, the memory of an insult may make us angrier than the insult did when we received it. Or, we may be more ashamed of our blunders afterwards than we were at the moment of making them.

The objects of most religions: A few Christians, for example, have had a sensible vision of their Savior, and enough appearances of this sort by way of the miraculous experience are on record to merit our attention later on in the lecture [the source of his book]. But, in addition to such circumstances, religion is full of theoretical, or conceptual, objects which prove to have equal power and influence.

![Immanuel_Kant_(painted_portrait)[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Immanuel_Kant_painted_portrait1-208x300.jpg) Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) says James, held a curious doctrine about such objects of belief: God, the soul, its freedom, its immortality, the design of creation, the life hereafter, etc. These things, Kant said, are not objects of knowledge at all, and our conceptions always require a [objective] sensory content to work with to be meaningful. Therefore, it follows that, theoretically speaking, they are mere words devoid of any significance. However, says James, they have a definite meaning for our practice. We can act is if there were a God; feel as if we were free; consider Nature as if It were full of special designs; lay plans as if we were immortal. And, we then find that these words do make a genuine difference in our moral life. So here we have this strange phenomenon, as Kant assures us, of minds believing with all their mental strength in the actual presence of a set of things from none of which can any concrete sensory perception notion be formed whatsoever.

Immanuel Kant (1724 – 1804) says James, held a curious doctrine about such objects of belief: God, the soul, its freedom, its immortality, the design of creation, the life hereafter, etc. These things, Kant said, are not objects of knowledge at all, and our conceptions always require a [objective] sensory content to work with to be meaningful. Therefore, it follows that, theoretically speaking, they are mere words devoid of any significance. However, says James, they have a definite meaning for our practice. We can act is if there were a God; feel as if we were free; consider Nature as if It were full of special designs; lay plans as if we were immortal. And, we then find that these words do make a genuine difference in our moral life. So here we have this strange phenomenon, as Kant assures us, of minds believing with all their mental strength in the actual presence of a set of things from none of which can any concrete sensory perception notion be formed whatsoever.

Recalling Emersonian Transcendentalism: James refers to the whole universe of concrete objects, or abstractions, as we know them swims, so-to-speak, not just for Emerson, but for all of us in a wider and higher universe of ideas that lends its significance. As space and time and “the ether” soak through all things we do feel abstracted from its essential goodness, justice, strength, power, and beauty. It gives to all Its Nature, thus all things their nature; their special thing. And everything we know is what it is by sharing in the nature of these abstractions.

For Plato (428- 348 BC) abstract Beauty is a definite, individualized thing. And, “the true order of going” is to use the beauties on Earth as steps along which one mounts upwards for the sake of that other Beauty, going from one to two, and from two to all fair forms, and from fair forms to fair actions, and from fair actions to fair notions, until he arrives at the notion of absolute Beauty and at last he knows what the essence of Beauty is.

(11)

Anyway, along slightly different lines:

James suggests, it is as if there were in the human consciousness a sense of reality, a feeling of an objective presence, a perception of what we may call “something there” beyond which our ordinary sensory perceptions supposes to be existent realities. An intimate friend of his, whom he refers to as one of the keenest intellects he knew, has had several experiences of this sort – a consciousness of a presence:

“It was about September, 1884, when I had the first experience. On the previous night I had, after getting into bed at my room in college, a vivid tactile hallucination of being grasped by the arm which made me get up and search the room for an intruder. This sense of presence, properly so called, came on again the next night. After I had gotten into bed and blew out the candle, I lay awake thinking of the previous night’s experience when suddenly I felt something come into the room and stay close to my bed. It remained but a minute or two. I did not recognize it by any ordinary sense and yet there was a horribly unpleasant sensation connected with it. The feeling had the quality of a very large pain spreading over my chest and yet, it was not so much a pain as an abhorrence. Something was present with me and I knew its presence far more surely than I have ever known the presence of any fleshy living creature. I was as conscious of its departure as I was of its coming; an almost instantaneously swift going through the door and the horrible sensation disappearing.”

“On the third night while absorbed in preparing some lectures I became aware of the presence (though not of its coming) of the thing that was there the night before and of the horrible sensation. I then mentally concentrated all my effort to charge this ‘thing’ if it was evil, to depart, if it was not evil, to tell me who or what it was and if it could not explain itself, to go. It then left as on the previous night. On two other occasions I have had precisely the same horrible sensation. Once it lasted a full quarter of an hour. The something seemed close to me, and intensely more real than any ordinary perception. Although I felt it to be like myself, so-to- speak; finite, small, and distressful, as it were. I didn’t recognize it as any individual being or person.”

Of course, such an experience as this does not tend to connect with the religious sphere yet, upon occasion, it may do so. The same correspondent informed James that on more than one other conjuncture he had the sense of a presence also developed with equal intensity and abruptness, only then it was filled with a quality of joy:

“There was not a mere consciousness of something there, but fused within the central happiness of it, was a startling awareness of some ineffable good. Not vague either, not like the emotional effect of some poem, or scenery, or of music, or blossom, but the sure knowledge of the close presence of a sort of mighty person. And, after it went, the memory persisted as the one and only perception of reality; that everything else might be a dream, but not that [presence].”

James states that his friend does not interpret these latter experiences theistically; as signifying the presence of God. But it would clearly not have been unnatural to interpret them as a revelation of God’s existence.

Similarly, a Professor Flournoy from Geneva gives James the following testimony of a friend of his, a lady, who has the gift of automatic writing:

“Whenever I practice automatic writing, what makes me feel that it is not due to a subconscious self, is the sensation I always have of a foreign presence external to my body. It is sometimes so definitely characterized that I could point to its exact position. This impression of such a presence is impossible to describe. It varies in intensity and clearness according to the personality from whom the writing professes to come. If it is someone whom I love, I feel it immediately before any writing has come. My heart seems to recognize it.”

(12)

James surmises that in the distinctively religious sphere of experience, many persons (and how many one cannot say) experience their belief not in the form of mere abstract concepts, but rather in the form of “quasi-sensible” realities directly comprehended. Here he cites an example of a negative one deploring the loss of the sense in question; extracted from an account given to James by a scientific man of his acquaintance:

“Between twenty and thirty I gradually became more and more agnostic and irreligious. I had ceased my childish prayers to God. Although I never prayed in a formal manner, but more like having been in a relationship with “It” which was practically the same thing as prayer. Whenever I had any trouble, especially conflicts with other people or when I was depressed in spirits or anxious about affairs, I used to fall back for support upon this curious relation which I then felt to be this fundamental cosmic “It.” It was on my side, or I was on its side, however you please to look at it, in the particular trouble. And, it always strengthened me and seemed to give me endless vitality to feel its underlying and supporting presence. It was an unfailing fountain of living justice, truth, and strength to which I instinctively turned to at times of weakness and it always brought me out. I know that it was a personal relationship I was in because now, years later, the power of communication with it has left me and I am conscious of a definite loss. I never used to fail to find it when I turned to it. Then came a set of years when sometimes I found it, and then again, other times when I would be wholly unable to make a connection. I would be unable to get to sleep on account of worry and in the darkness I groped mentally for that higher mind of my mind which had before seemed always to be close at hand, yielding support, but there was no electric current; a blank was there instead of It. Now, at the age of fifty, I have to confess that a great help has gone out of my life. Life has become curiously dead and indifferent. I can now see that my earlier experience was probably exactly the same thing as prayers, only I did not call them by that name. Although I have spoken of it as “It,” it was my own instinctive and individual God whom I relied on for higher understanding but whom somehow I have since lost.”

James now informs us that the adjective “mystical” is generally applied to states that are of brief duration and we shall here cite a couple of cases. The immediate one is an abridged version [by James] of a mystical or semi-mystical experience of a mind, as he puts it, “evidently framed by nature for ardent piety.” The lady who gives the account was the daughter of a man well known in his time as a writer against Christianity. She relates that she was brought up in entire ignorance of Christian doctrine but, while in Germany, after being talked to by Christian friends, she read the Bible and prayed, and finally the plan of salvation flashed upon her like a stream of light:

“To this day, I cannot understand dallying with religion and the commands of God. The very instant I heard my Father’s cry calling unto me, my heart bounded in recognition. I ran, I stretched forth my arms, I cried aloud, “Here, here I am my Father, what should I do?” “Love me, answered my God.” “I do, I do!” I cried passionately. “Come unto me,” called my Father. “I will!” my heart panted. Did I stop to ask a single question? Not one. It never occurred to me to ask whether I was good enough, or to hesitate over my unfitness, or … to wait until I should be satisfied. Satisfied? I was satisfied! Had I not found my God and my Father? The idea of God’s reality has never left me for one moment.”

(13)

Here is another case, the writer being a man aged twenty-seven:

“I have on a number of occasions felt that I had enjoyed a period of intimate communion with the Divine. These meetings came unasked for and unexpected. Once it was from the summit of a high mountain. Beneath me and beyond was a boundless expanse of white cloud cover. And, on the blown surface a few high peaks, including the one I was on, seemed to be plunging about as if they were dragging their anchors. What I felt, on this and other occasions, was a temporary loss of my own identity accompanied by an illumination which revealed to me a deeper significance then that which I had been previously inclined to attach to life. It is in this that I find my justification for saying that I have enjoyed communication with God. Of course, the absence of such a being as this would be chaos. I cannot conceive of life without its presence.”

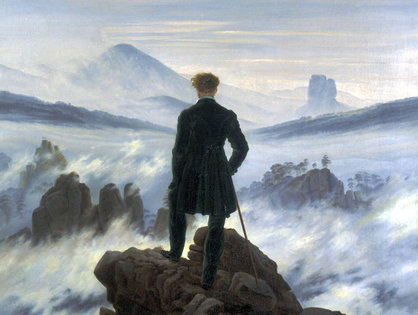

“Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Von Caspar David Friedrich

“Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog” by Von Caspar David Friedrich

James here speaks of the convincingness of these feelings of reality and elaborates further stating that they are as convincing to those who have them as any direct physically sensible experiences can be, and they are, as a rule, much more convincing than results established by mere logic ever could be. Nevertheless, if we look on man’s whole mental life and, on that life within them that is apart from their learning and science; on that which they inwardly and privately follow, we have to admit that the part of life, which rationalism can give an account of, is relatively superficial. Yet, it [rationalism] is undoubtedly the part that has the prestige. After all, it also has the loquacity; it can challenge you for proofs, chop with its logic and put you down with words. Regardless, it will fail to impress, convince, or convert you all the same should your dumb intuitions be opposed to its brilliant conclusions. For, if one has intuitions at all, they know that they come from a deeper level of one’s nature than the loquacious level in which rationalism resides. And, something in the individual absolutely knows that the result must be truer than any logic-chopping rationalistic talk, however clever, that may contradict this knowing. In the metaphysical and religious sphere, articulated reasons are cogent only when our inarticulate feelings of reality have already been impressed upon us. James implores us here to note that he does not hold the opinion that it is better that the subconscious and non-rational should hold primacy in the religious realm. But rather, what he does state, is that they just do so as a matter of fact.

(14)

Lectures IV and V – THE RELIGION OF HEALTHY-MINDEDNESS

The author begins this lecture posing the question: “What is human life’s chief concern?” He then states that one of the answers we should receive would be “It is happiness.” Therefore, it is not surprising that some come to regard the happiness which religious belief affords as a proof of its validity. Here he cites a German writer:

“The near presence of God’s spirit may be experienced in its reality – indeed only experienced. The Spirit’s existence and nearness are made irrefutably clear to those who have had the experience. It is the feeling of supreme happiness which is connected with this nearness and, which is not only possible but an altogether proper feeling for us to have here below [on the earthly plane], that is the best and most indispensable proof of God’s reality. Therefore, happiness is the point from which every efficacious new theology should start.”

In some, James claims, happiness is congenital and, he speaks not only of those who are animally happy but those whom, when unhappiness is offered or proposed to them, they positively refuse to feel it as if it were something mean and wrong. He goes on to say, we find such persons in every age, passionately flinging themselves upon their sense of the goodness of life in spite of the hardships of their own predicament and in spite of the sinister theologies into which they may have been born. It is probable, he theorizes, that there never has been a century in which the deliberate refusal to think ill of life has not been idealized by a sufficient number of persons who form sects, open or secret, and who claim all natural things to be permitted. Saint Augustine’s maxim, if you but love [God], you may do as you incline – is morally one of the profoundest of observations. Although, for some, it is pregnant with passports allowing for what is far beyond the bounds of conventional morality according to their characters; be they refined or gross. God, for them is a giver of freedom and the sting of evil thus overcome.

These same personalities generally have no metaphysical, introspective tendencies; they do not look into themselves. They are not distressed by their own imperfections. Yet, it would be absurd to call them self-righteous for they hardly think of themselves at all. This child-like quality of their nature makes the deity of a religion very happy to them; for they no more shrink from God than a child from an emperor before whom the parent trembles. This straight and natural “once-born” type of consciousness, with no element of morbid compunction or crisis, is contained in an answer to one of Dr. Edwin Starbuck’s questionnaires by the eminent Unitarian preacher and writer, Dr. Edward Everett Hale. [I shall mention here that Professor Edwin Starbuck, author of “The Psychology of Religion,” provided William James with several of the examples of the experiences and opinions referred to in his book, and therefore in this abridged version].

Dr. Hale: “I was born into a family where the religion was simple and rational. I always knew God loved me and I was always grateful to Him for the world he placed me in. I always liked to tell Him so and was always glad to receive His suggestions. I can remember perfectly well that when I was coming into manhood, the half-philosophical novels of the time had much to say about the young men and maidens who were facing the ‘problem of life’. I had no idea what the ‘problem of life’ was. To live with all my might seemed to me easy. A child who is taught early that he is God’s child and that he may have his life, his movement, his being in God, he therefore has at hand infinite strength for the conquering of any difficulty. And, will thus take life more easily and probably make more of it …”

(15)

Yet, on a slightly different note, James adds, the finding of a luxury in a state of woe is very common during adolescence and here a Marie Bashkirtseff expresses it quite well in her journal:

“In this depression and dreadful uninterrupted suffering, I don’t condemn life. On the contrary, I like and find it good. I find everything good and pleasant, even my tears, my grief. I enjoy weeping, I enjoy my despair. I enjoy being exasperated and sad. I cry, I grieve, and at the same time I am pleased – no, not exactly that – I know not how to express it. I find everything agreeable and in the very midst of my prayers for happiness I find myself happy at being miserable.”

![220px-Whitman_at_about_fifty[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/220px-Whitman_at_about_fifty1-198x300.jpg) The next example we get is that of the poet Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892) whom James claims to be the supreme ‘contemporary’ example of an individual wholly unable to perceive evil. Here James provides a rather long passage of what was professed to be Whitman’s most sincere belief in the innate and divine goodness in everyone and everything. Instead, for the sake of brevity (this is an abridged version after all) I shall take the liberty of providing a few quotes of Whitman’s that adequately exemplify the point here made:

The next example we get is that of the poet Walt Whitman (1819 – 1892) whom James claims to be the supreme ‘contemporary’ example of an individual wholly unable to perceive evil. Here James provides a rather long passage of what was professed to be Whitman’s most sincere belief in the innate and divine goodness in everyone and everything. Instead, for the sake of brevity (this is an abridged version after all) I shall take the liberty of providing a few quotes of Whitman’s that adequately exemplify the point here made:

“Give me the splendid silent sun, with all his beams full-dazzling. Keep your face always towards the sunshine and the shadows will fall far behind you.”

“Youth, large, lusty, loving – youth, full of grace, force, fascination. Do you not know that old age may come after you with equal grace, force and fascination?”

“I know nothing grander, better than exercise, good digestion, more positive proof of the past, the triumphant result of faith in human kind, than a well-contested American national election.”

L.T. – I don’t believe U.S. elections are at all legitimate anymore [12/26/22]. Maybe they never were. Years ago a woman told me of election fraud she witnessed in her county the early 1990s and I thought how naive I’ve been. Regardless, I shall include a few quotes from Alice Roosevelt Longworth (1884 – 1980) the daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt.![180px-Alice_Roosevelt_LOC_USZ_62_13520[1]](https://miraclesforall.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/180px-Alice_Roosevelt_LOC_USZ_62_135201.jpg)

“If you haven’t got anything nice to say about anybody, come sit next to me.”

Of her father, whom she said, insisted upon being the center of attention everywhere he went: “My father always wanted to be the corpse at every funeral, the bride at every wedding and the baby at every christening.”

When asked by a Ku Klux Klansman to take his word for something, she refused saying “I never trust a man under sheets.”

We now return to the book and here James informs us: Thus it came to pass that many persons [in his day] regarded Walt Whitman as the restorer of the eternal natural religion. He had infected them with his own love of comrades; with his own gladness that they and he existed. Societies were actually formed for his cult. A periodical existed for the society’s propagation in which the lines of orthodoxy were drawn. Hymns were written by others in his peculiar poetic metric. And, he was even being explicitly compared with the founder of the Christian religion. Whitman was often spoken of as a “pagan” which [then] sometimes meant the mere natural animal man without a sense of sin and, sometimes it meant a Greek or Roman with his own uniquely personal religious consciousness. Although James claims that neither of these definitions aptly apply to the poet for he was more than your mere animal man who had not tasted the tree of good and evil. And, according to James, he was well aware enough of sin for a swagger to be present in his indifference towards it, which your genuine pagan, in the first definition of the word, would never show.

James also states that Whitman was less than a Greek or Roman, for their consciousness was full to the brim of the sad mortality of this sunlit world; a consciousness Walt Whitman resolutely refused to adopt. The Romans and the Greeks kept their sadnesses and gladnesses unmingled. Nor did they recon sin feeling a need to credit the universe, as so many of us insist upon doing, by claiming that what evidently appears as evil must be “good in the making” or something equally ingenious. For the early Greeks, good was good and bad was just bad. They did not deny the ills of nature as is the case in Walt Whitman’s verse, “What is called good is perfect and what is called bad is just as perfect,” for this would have been mere silliness to them. Nor did they, in order to escape from those ills, invent “another and a better world” of their imagination.

L. T. – I learned this about Walt Whitman from author Naomi Wolf:

“Whitman, a poet taught now in high schools, was utterly vilified, as we often forget, in his own lifetime. By the mass media of his day, by the important critics and by the government spokespeople, he was called: insane, filthy; and the Victorian equivalent of “unhinged”; poisonous, dangerous, profane; disgusting. His books were illegal to print in Britain, and then were made illegal to transport through the mails in the United States. He lost his comfortable job in the government. His health failed. His publisher abandoned him. He sustained a stroke, and was partly paralyzed. He was, finally, so broken in health, and so very poor, that his supporters overseas had to send around a begging letter to get him some charity.”

“And yet. And yet. He kept telling his truth.”

“Censored in two nations, he had a book being readied for publication on the day that he died.”

“And ultimately, Walt Whitman was not silenced – because history shows there is really no such thing as censorship. Because the truth always emerges at last.”

“Because love always wins.”

(16)

L. T. – Now back to James:

Systematic healthy-mindedness: Conceiving good as the essential and universal aspect of being which deliberately excludes evil from its field of vision.

Although, when thus nakedly stated, this might seem a difficult feat to perform for one who is intellectually sincere with themselves and honest about the facts, a little reflection shows that the situation is too complex to impart so simple a criticism. James observes that when happiness is the current state of mind, the thought of evil can no more acquire the feeling of reality than the thought of good can gain reality when melancholy rules.

Yet, much of what is considered evil is entirely due to the way the phenomena is perceived. Once faced, it can often be converted into a bracing and restorative good by the sufferer’s change of attitude from one of fear to one of fight; its painfulness turns into a relish when, after vainly seeking to ignore the evil, it is embellished with a new temperament bound in honor; the evil is swallowed up as an omnipotent excitement which the human being then embraces. This, they will say, is to truly live and they exalt in the heroic opportunity and adventure of combating the evil.

In Christianity, the advance of liberalism, so called, may well be a victory for healthy-mindedness within the church over the old morbid hell fire theology. We now have whole congregations whose preachers, far from magnifying our consciousness of sin and evil, they ignore, deny even, eternal punishment and insist on the dignity rather than the depravity of man. These persons, however, maintain their connection with Christianity despite their discarding of its more pessimistic theological elements.

Accordingly, we also find “evolutionism” interpreted thus optimistically and embraced as a substitute for the religion they were born into by a multitude of our contemporaries [still true in our time as it was in James’ although many now refer to it as “scientism”] who have either been trained scientifically or are fond of reading popular science. Below he quotes from a document he received in answer to Professor Starbuck’s circular of questions. The writer’s state of mind may be loosely called a religion of sorts, for it is his reaction on the whole of nature. It is systematic and reflective. James says we shall recognize in him a sufficiently familiar contemporary type, [which we do of course]:

Q. What does Religion mean to you?

A. It means nothing and it seems, so far as I can observe, useless to others. I am sixty seven years of age and have been in business forty-five, consequently I have some experience of life and men, and some women too, and I find that the most religious and pious people are as a rule those most lacking in uprightness and morality. The men who do not go to church or have any religious convictions are the best. Praying, sermons, singing hymns are pernicious – they teach us to rely on supernatural powers when we out to rely on ourselves. I totally disbelieve in a God. The God idea was begotten in ignorance, fear and a general lack of any knowledge of nature. If I were to die now … I would die as a timepiece stops – there being no immortality.

Q. Have you had any experiences which appeared providential?

A. None whatever. There is no agency of the superintending kind. A little judicious observation as well as knowledge of scientific law will convince anyone of this fact.

Q. What comes to your mind corresponding to the words God, Heaven, Angels, etc.?

A. Nothing. I am a man without religion. These words being merely mythic bosh.

Q. What is your temperament?

A. Nervous, active, wide-awake mentally and physically. Sorry that Nature compels us to sleep at all.

James posits that we have in this man an excellent example of the [so called] rationalism, which may be encouraged by popular science.

(17)

To the author however, far more important and interesting religiously than that which sets in from natural science is what he refers to as the “Mind-Cure” movement. He goes on to mention that there are various sects of the “New Thought” (to use another name by which it calls itself) movement that is sweeping throughout America and gathering force every day [and still is a hundred years since if it be the same as “New Age” spirituality or perhaps the “Power of Positive Thinking” practitioners of today, or both]. He goes on to say that this movement had reached the point when the demand for its literature was great enough for superficial insincere stuff, mechanically produced for the market, to be supplied by publishers [that too continues to this day!].

The leaders in this faith propose belief in the all-saving power of healthy-minded attitudes such as: the conquering efficacy of courage, hope and trust along with a correlative contempt for doubt, fear, worry and all nervously precautionary states of mind. James here boldly mentions results of no less than remarkable restorations of health and healing from invalids to the blind, a regeneration of the general uplifting of character on an extensive scale, and adds that cheerfulness has been restored to countless homes.

L.T. – In other works, I have read how the spread of Darwinism and scientism at this time delivered a striking blow to the Biblical account of creation as set forth in the “Book of Genesis” and therefore people’s religious faith in general. The result being, that the baby was thrown out with the bath water, so-to-speak, by the new scientific theories and their proponents – all religious belief was considered “bosh” as the fellow quoted above claimed. Evolutionism, or Darwinism, along with the “death of God” as decreed by Friedrich Nietzsche led to a period of despair and hopelessness for many in the latter half of the 19th century.